Fannie and Freddie

take a big hit as their debt gets shunned in a market auction, taking

another big step towards the ultimate taxpayer bailout. Banks are

scrambling to raise cash – along with everybody else. Credit crisis,

anyone? And market insiders are starting to openly discuss the weird

market ‘behavior’ of late, which I merely shrug at and consider to be

evidence of something we’ll read about when Hank Paulson writes his

memoirs in 10 years.

August 18

Freddie Mac debt sale weak, bailout concerns rise (August 18 – Reuters NEW YORK)

Investors dumped the stocks of Fannie Mae and

Freddie Mac on Monday after Barron’s reported the increasing likelihood

of a U.S. Treasury bailout that would approach nationalization of the

two housing finance titans.

The weekly financial newspaper

said such a move could wipe out existing holders of the largest U.S.

home funding companies’ common stock. Preferred shareholders and even

holders of the two government-sponsored entities’ $19 billion of

subordinated debt would also suffer losses.

If the GSEs fail

to raise fresh capital, the administration is likely to mount its own

recapitalization, with the Treasury infusing taxpayer money into the

agencies, according to the Barron’s source. The report said an equity

injection by the government would be a quasi-nationalization — without

having to put the agencies’ liabilities on the U.S. balance sheet, and

thus doubling U.S. debt.

As expected,

and utterly without any surprise at all, we note that each week brings

us one step closer to outright nationalization of Fannie and Freddie.

In this

article it is noted that Freddie’s most recent bond auction went

poorly, raising the risk that the cost of borrowing would climb for the

GSE, leading to lower profits, higher mortgage rates, and ultimately a

higher risk of outright default.

As always,

the messenger is being shot. In this case, the blame for the poor

auction results is being pinned to a hard-hitting Barron’s article,

which took a realistic look at Fannie and Freddie and found them to be

insolvent, and also came to the conclusion that together they were most

likely already worth negative $100 billion, or -$50 billion each.

But even this is overly optimistic.

Together

they hold, or are guaranteeing, a combined portfolio of mortgages of

over $5 trillion dollars. This means that for each 1% of decline in the

value of those portfolios, another $50 billion is lost. Given that this

will be the largest housing bubble to ever burst, I fully expect to see

larger losses than any ever experienced before.

I would not be surprised to see losses in the 5% to 10% range.

This would

translate into a taxpayer bailout in the vicinity of $250 to $500

billion dollars … just for these two companies. Now, when we add in

Citi, GM, a couple of large hedge funds, and numerous other companies

“too large to fail,” couple these to the desire to “do something” (i.e.

print), you can begin to appreciate why I am bearish on the dollar and

bullish on inflation hedges. Do you find yourself wondering if some of

these companies should be allowed to fail?

You’re in good company. See next.

Bernanke Tries to Define What Institutions Fed Could Let Fail (Aug. 18 – Bloomberg)

Ben S. Bernanke is still trying to define which

financial institutions it’s safe to let fail. The longer it takes him

to decide, the tougher the decision becomes.

In the year since

credit markets seized up, the 54-year- old Federal Reserve chairman has

repeatedly expanded the central bank’s protective role, turning its

balance sheet into a parking lot for Wall Street’s hard-to-finance

bonds and offering loans through its discount window to investment

banks and mortgage firms Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The lack of

clearly defined limits may put the Fed’s independence at risk as

Congress discovers that its $900 billion portfolio can be used for

emergency bailouts that might otherwise require politically sensitive

appropriations and taxes.

In some respects, it’s already too late.

Bear Stearns

should have been allowed to fail. Because it wasn’t, we can deduce that

the degree of leverage and interconnection of the financial system is

now deemed to be too large to allow even a decidedly medium-sized

player to go under. So the Fed’s hand is tipped. We can surmise that

the mountain of derivatives that the Fed allowed to blossom under its

wavering eye over the past 8 years are now beyond its comprehension,

and it fears an uncontrollable market reaction should that mountain

crumble.

Unfortunately,

Congress has certainly set its eye on the magic ability of the Fed to

simply print money to pay for fixes, and this is a bad thing,

especially in an election year. I say unfortunately, because this is

how fiat money always meets its end – with “emergency bailouts that

might otherwise require politically sensitive appropriations and

taxes.”

It’s always

a bad time to make difficult decisions and/or raise taxes. That’s just

part of being human. The only thing, at this point, that would make me

change my views, would be if Paul Volker (former Fed Chairman who

raised interest rates to 21% back in the 80s) was brought back in to

lead the Fed.

But at this point?

I am resigned to the near-certain destruction of the dollar by a process of massive over-printing, leading to inflation.

US banks scramble to refinance maturing debt (August 17 – FT)

Battered US financial groups will have to refinance

billions of dollars in maturing debt over the coming months, a move

likely to push banks’ funding costs higher and curb their

profitability, say bankers and analysts. The banks’ need to raise

capital to offset mounting credit-related losses is forcing them to pay

higher interest rates to entice investors.

Adding together 10

of the biggest bank borrowers, Dealogic said that maturing bonds total

$27bn in August, $52bn in September, $23bn in October, $20bn in

November and $86bn in December. The extent of the scramble for funds

became clear last week when banks tapped central lending facilities,

with strong demand for one- and three-month money lent by the Federal

Reserve and the European Central Bank. US commercial banks borrowed a

record daily average of $17.7bn from the Fed last week.

This is also known as “the spiral of death”.

Banks all need

more funding, but (and this is the funny part) banks are the source of

funding. So higher borrowing needs result in higher costs for

borrowing, which lead to higher costs, and so forth, until their

profitability is entirely destroyed and they go bankrupt.

But it’s not

just the banks that will be scrambling and competing for capital over

the next 5 months. They will be in competition with the US Government,

Fannie and Freddie, corporations, and states, even as foreign investors

and banks are going to be feeling slightly less flush due to an overall

weakening economy.

This raises

the most dreaded prospect of them all – that the US might have to rely

on its own savings to fund this borrowing spree. Dreaded, because there

really isn’t much there to borrow.

No Credit for Financials, Part 2 (August 18 – Bennet Sudacca in Minyanville)

Many days, I feel that, even if you’d given me

tomorrow’s economic headlines a day in advance, the stock market would

still do something contrary to what I would’ve been positioned for.

Mind you, I don’t feel all warm and fuzzy admitting this fact, but

there’s been a random tone to equities of late, particularly sectors

and commodities.

Last Thursday morning, I came in to work

positioned for a hotter-than-expected CPI report and a very weak

unemployment report. My firm got both right – really right. One would

think that stocks — particularly retailers and anything in the

‘consumer discretionary” area — would get hammered, but instead they

rallied fiercely.

Is this a function of being short the

consumer – a “crowded trade”? Most likely, but it makes one wonder how

S&P futures magically rally on bad economic news. In fact, it seems

like the worse the news, the stronger the rally. I’ll leave it to

“conspiracy theorists” as to why this is happening, but markets do

eventually find the “right” level.

While I am an

economic commentator who sits on the outside peering in, Bennet Sudacca

runs a fund and is inside the game. We both note, with growing

puzzlement and concern, that our financial markets seem to be running

counterintuitively lately.

Where we depart is

that I will come right out and say that it is quite clear to me that

there is no clear line between official interventions that have been

openly announced and those that have not. The perception of health in

our financial markets is clearly both economically and politically

important.

In an age where every

message is spun, each bit of data controlled, it is simply

inconceivable to me that something as important as the financial

markets would be left alone. Especially during election season.

Where we agree is that

I concur with the sentiment that markets always find their right level.

And where I grow concerned is that, by forcing markets into unnatural

territory, these acts of intervention are increasing the risk of a

sudden, dramatic correction, like a large block of ice that is fumbled

before it can be placed overhead.

The PPI and Housing

data were decidedly bearish, both hitting multi-year extremes, while

more pontificators are now guessing that a major financial accident

still lies in wait. The top five oil majors are down a collective

600,000+ barrels of oil production, which is more than the largest oil

field brought on line by Saudi Arabia in the past 2 years. Looks like

we need to find another couple of Saudi Arabias lying around.

August 19

Wholesale prices: Highest annual rate in 27 years (August 18 – CNNMoney)

In another indication of growing inflation,

wholesale prices increased in July to the highest annual rate in 27

years, according to a government report released Tuesday. The annual

Producer Price Index for finished goods rose 9.8% in the 12 months that

ended in July.

You are

already familiar with the CPI, which (supposedly) measures the

inflation experienced by the typical consumer. This report from the BLS

measures the Producer Price Index (PPI) which is a measure of inflation

experienced by companies at each stage of the manufacturing and

delivery process.

A nearly 10%

reading is pretty bad, because we can be sure that it is at least 5% to

8% higher than that. For example, I seriously doubt Dupont would have

raised prices by 25% last July if they were experiencing 9.8%

inflation. You can trust that the PPI is subject to the same sort of

Fuzzy Number treatment applied to the CPI, GDP, and other government

statistics.

Yet again,

the very first response of the market was to dump gold, the inflation

hedge, hard (since reversed). Who is it that sells gold that hard on

first news of a bad inflation reading?

I’d like to meet them.

Large U.S. bank collapse seen ahead (August 19 – Reuters)

The worst of the global financial crisis is yet to

come and a large U.S. bank will fail in the next few months as the

world’s biggest economy hits further troubles, former IMF chief

economist Kenneth Rogoff said on Tuesday.

"The U.S. is not out

of the woods. I think the financial crisis is at the halfway point,

perhaps. I would even go further to say ‘the worst is to come’," he

told a financial conference.

"We’re not just going to see

mid-sized banks go under in the next few months, we’re going to see a

whopper, we’re going to see a big one, one of the big investment banks

or big banks," said Rogoff, who is an economics professor at Harvard

University and was the International Monetary Fund’s chief economist

from 2001 to 2004.

"We have to see more consolidation in the

financial sector before this is over," he said, when asked for early

signs of an end to the crisis.

This is just

one man’s opinion, and an economist’s at that, but one with which I

happen to partially agree. No good crisis is ever over until you have a

“market clearing event.” This would be some form of shocking event,

like the collapse of Enron, that really puts the fear into people.

We haven’t

had that yet, and I would be incredibly surprised if we managed to

skate past the implosion of the largest credit bubble in all of history

without such an event. It simply strains credulity to suggest otherwise.

Single-family housing permits fall to 26-year low (August 19 – MarketWatch)

U.S. home builders sharply reduced the number of

new homes starting construction in July and dropped the number of new

single-family permits to the lowest level in 26 years, the Commerce

Department estimated Tuesday.

Housing starts fell 11% to a

seasonally adjusted annual rate of 965,000 in July, close to the

960,000 expected by economists surveyed by MarketWatch. See Economic

Calendar.

It marked the lowest level for housing starts in 17

years. June’s starts were revised higher to a 1.084 million annual

pace. Housing starts are down 29.6% in the past year.

We’re

getting there. However, even with this rather large drop in housing

construction, the pace is still pretty closely matching sales activity,

which means the large overhang of excess supply is still sitting out

there. To work it off we’ll need to see several quarters of home

construction that are well below the pace of new home sales.

One other

thing, try not to act surprised when the next employment report shows

residential construction employment to be vastly higher than it was 17

years ago. And then don’t forget to remain calm when the next

productivity report shows another smart advance.

The US; the only country that can build the same number of houses with twice as many workers while simultaneously reporting a tidy increase in productivity. Now that’s a neat trick.

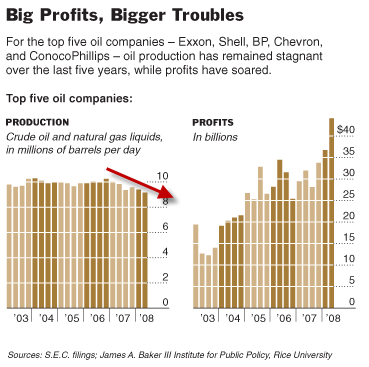

As Oil Giants Lose Influence, Supply Drops

Oil production has begun falling at all of the

major Western oil companies, and they are finding it harder than ever

to find new prospects even though they are awash in profits and eager

to expand.

The scope of the supply problem became more clear

in the latest quarter when the five biggest publicly traded oil

companies, including Exxon Mobil, said their oil output had declined by

a total of 614,000 barrels a day, even as they posted $44 billion in

profits. It was the steepest of five consecutive quarters of declines.

The pace of

production declines in post-peak areas are accelerating, whether

measured at the company level, as above, or by countries (Mexico) or

specific oil regions (North Sea).

On the one hand we might suspect

that top oil companies are ‘holding back’ figuring they are earning

enough profits and therefore the production declines are an act of

management, not geology.

On the other hand, we might note that

such restraint has never been displayed by these same companies in the

past, even when oil was $10 a barrel, which provides an enormous

incentive to leave it in place.

I take this as just further confirmation that we are past peak for the majority of known countries and projects (by volume).

The data just keeps piling up. The implications are enormous.