Thursday, October 9, 2008

In this Martenson Report, I cover the importance of the credit markets to the smooth functioning of our just-in-time economy. If the credit markets fully seize up, it is not a stretch to state that most businesses and the flow of many goods will also seize up.

In fact, this has already happened, to a limited extent. Should this extend further, there are a few basic precautions that you should consider as a means of mitigating the impact of a potential banking/credit lock-up.

Okay, time for a little chat about the reasons that a credit market freeze-up has the potential to change your life in sudden and dramatic ways.

Many people mistakenly believe that at some point in the distant past we moved from a barter economy to a money-based economy. In truth, we have a credit-based economy.

In a money-based, or “cash-based,” economy, the whole thing would work a lot like your debit card. Businesses would immediately swap money for goods at the point of the transaction.

But that’s not how our system operates. Instead, when goods flow between distributors, suppliers, and retailers, they do so on the basis of credit. For example, if your local grocery chain orders additional food from their distributor, credit is what gets that transaction moving right away. The grocery store has a line of credit with the distributor, which has a line of credit with their bank, which has lines of credit with other banks, one of which has a credit arrangement with the grocery store.

Typically, businesses carry 30-60-90-day terms on cash settlement for goods and services sent/received. So the lines of credit are an important ‘lubricant’ to the process of buying and selling goods, with cash settlement coming after-the-fact and often comprising a bulk payment for numerous credit-based transactions that might have occurred over a period of time.

At the larger level, credit transactions worth trillions of dollars are occurring between importers and exporters, with municipality paychecks, between nations, in stock margin accounts, and so forth. Credit is everywhere and it is how we conduct business. Without credit, we’d need to revert to a cash-based economy (hard cash or the electronic equivalent) and the simple fact is that our financial and judicial machinery are just not set up to handle a cash-based economy. They could be, I suppose, but right now they aren’t.

So we need to ask ourselves, “What will happen if the credit markets completely freeze up?” Here’s an example from Tuesday (Oct 7th, 2008), neatly illustrating the confusion and stasis that results from a credit market seizure:

The credit crisis is spilling over into the grain industry as international buyers find themselves unable to come up with payment, forcing sellers to shoulder often substantial losses.

Before cargoes can be loaded at port, buyers typically must produce proof they are good for the money. But more deals are falling through as sellers decide they don’t trust the financial institution named in the buyer’s letter of credit, analysts said.

"There’s all kinds of stuff stacked up on docks right now that can’t be shipped because people can’t get letters of credit," said Bill Gary, president of Commodity Information Systems in Oklahoma City. "The problem is not demand, and it’s not supply because we have plenty of supply. It’s finding anyone who can come up with the credit to buy."

In the article above there are willing buyers and sellers but believable bank credit is the missing element.

Banks are essential intermediaries in a credit-based system, and the flow of goods comes to a shuddering halt without available, and, most importantly, believable credit. Sure, I suppose it is possible for a buyer to wire over the cash money to release the goods, but that type of exchange takes a different form of trust that is very likely to be in short supply during a crisis. Who would want to send off money without a system of assurances that the products will be shipped? Where there is an entire system of checks and balances erected around credit transactions, there are fewer for cash transactions.

Think of an Ebay auction where you use your credit card vs. sending off cash in an envelope. If the deal goes bad, you have more options for recourse under the credit transaction than the cash transaction. This is also true for businesses of every size.

This is why the recent decision to allow banks to “mark (all of their toxic assets) to maturity” was a bad move. While it helped the balance sheets appear to be healthier, which I am sure made some CEOs happy, it also served to make the banks’ financial positions less transparent, causing an offsetting erosion of confidence. After this move there is now less certainty about anyone’s solvency. And so our credit markets are seizing up, and grain is not being shipped from docks. On the surface this may not seem like a huge problem, but once you understand how our entire economy is predicated on a “just in time” delivery system, the problem is obvious. A couple of examples:

- Grocery stores typically only have 3-5 days of food on hand. The continuous arrival of new trucks on a daily basis is essential to keeping them supplied. Credit allows this to happen.

- The US imports 17% of its daily gasoline needs from foreign refiners. Credit allows this to happen.

Literally every single supply chain in our complicated consumer network is dependent on the smooth functioning of the credit markets. (Okay, maybe not the illegal drug market, but you get the drift.) While it is possible to switch to a cash-based scheme for normal business transactions, that process will take time, possibly years, and the credit markets are currently imploding at a rate that suggests we have only a few weeks to sort all this out.

This is what is happening behind the scenes, and this is why the Treasury Department and the Federal Reserve are operating in such a panic mode.

In a larger sense, what we are seeing is the inevitable result of a fractional reserve banking system that has burned itself out. In 2003, Alan Greenspan reduced the US interest rate to the emergency level of 1% and held it there for a year. The rest of the world’s central banks followed suit, and the rest is history.

As a result, we had the greatest expansion of debt that the world has ever seen. Credit bubbles always end in a bust, and they do not end until all of the prior excesses are wrung out of the system. For the US, this presents quite a tricky bit of landscape to navigate, because we mainly financed our excesses through foreign borrowing. Plus, we still own the world’s reserve currency. Together these facts compound the difficulty of managing a successful conclusion to the crisis.

So we are now forced to admit, at least to ourselves, that it is now possible that both the dollar and the entire fractional reserve banking system could implode.

In the case of the dollar, trillions and trillions of them are now held by foreigners. In order for the dollar to merely maintain its value internationally, foreigners must keep buying it at the same pace as before. If they continue to maintain their current dollar positions, but stop buying more, the dollar will fall. If they stop buying more and decide to unload the ones they already have, then the dollar will crash.

We have, in essence, three generations of excess spending out there in the hands of foreign nations, some of them openly hostile to the US. Our future rests upon their kindness. In the case of the banking system, it is already, obviously, in terrible shape. The entire network, in aggregate, is insolvent. The damage in several key financial stocks this week has been staggering, if not frightening.

Recalling my earlier statement about “marking to maturity,” we can see evidence of the resulting level of concern by viewing the stock price of Citigroup, which holds slightly more than $1 trillion (with a “t”) of the so-called “Level III” assets, which are equivalent to the “marked-to-maturity” assets that I spoke of earlier. Here we can see that Citigroup is rapidly approaching its recent lows, having lost all of the momentum that the “no short” rule change gave it a while back:

And here are several other major insurers that are certainly going down soon. MetLife starts the ball rolling here:

That chart, my friends, is a complete disaster. Something is very broken at MET that will require a lot of fixing. MET “…offers life insurance, annuities, automobile and homeowners insurance, retail banking and other financial services to individuals, as well as group insurance, reinsurance and retirement and savings products and services to corporations, and other institutions."

And here’s Prudential Financial. This, too, is a very ugly chart:

PRU “…offers an array of financial products and services, including life insurance, annuities, mutual funds, pension and retirement-related services and administration, investment management, real estate brokerage and relocation services, and, through a joint venture, retail securities brokerage services.”

And here’s Aegon, a major holding company offering insurance, pension, and financial services and products. This chart shows the complete breakdown of yet another gigantic company with financial tendrils that reach far and wide:

And here’s the last one, Hartford Financial Services (HIG – primarily an insurance company), slightly larger than AEG but smaller than MET:

These are all gigantic companies, each as large as Enron and each with charts indicating that utter failure is just around the corner. We can all hope that a financial rescue is in the works that will be able to fix all of this, but we’d be better off planning as if that weren’t going to happen.

What you can do about this

First, I want you to accept the possibility that the entire banking system could go into a form of financial cardiac arrest and fail to work properly. If this happens, uncertainty and fear will rule the day. Jobs will be lost, goods will grow scarce, and rumors will fly.

The most obvious impacts will be felt locally. Towns, municipalities, and states will have to navigate the loss of significant portions of their budgets. Services will be cut. Some stores and supply channels will not be able to operate, either because their cash flow got pinched and they went out of business as a result, or because their credit facilities dried up and prevented normal operations. Some goods will rapidly become scarce.

The first step in preparing yourself for this scenario is to understand why this has happened. By taking the Crash Course, you already know the mechanics of this situation and that everything that the Treasury and Fed are trying to fix (at least publicly) are merely symptoms. The cause was a 25-year-long credit binge that finally ran out of steam.

The second thing you can do is to adopt a highly defensive posture with respect to money and your basic living arrangements. Let me reiterate the basic Tier I actions that you should all have taken by now:

- Trim your expenses as far as humanly possible.

- Keep cash out of the bank. Three months’ living expenses if you can; otherwise as much as possible.

- Do you have essential medicines that you count on? If it’s possible, keep an extra supply around the house.

- When you can, keep things topped off around the home. I recommend keeping at least a three-month supply of food on hand, in case the trucks stop rolling for any reason. I know this may sound “out there” for some of you, and if this goes too far in your mind, simply ignore it. But for anybody who has even the slightest worry in this regard, when all is said and done it takes relatively little effort and no extra money to make this fear go away. I say “no extra money,” because you would eventually have bought and eaten the food anyways. Through all of human history, up until about 50 years ago, it would have been unthinkable for the average family not to know exactly where its food for the winter was located. Our modern dependence on just-in-time delivery is a very, very recent development, and one for which we may potentially pay a very high price

- Hold gold and silver, physical only. How much? That depends on how many of your US-dollar-denominated holdings you’d like to be absolutely sure do not go to zero.

And here are the Tier II actions that you should consider in preparing for a potential credit market collapse:

- Develop a sense of community and get to know the people you can count on and who will count on you.

- Don’t take on any more purely consumptive debt for any circumstances, unless you are speculating and can manage the risks. This means you should not buy a house that is a stretch, you should make the old car go a little longer, and you should not be putting anything on the old credit card that you cannot find a way to do without.

- Keep your job! I don’t care how much you hate your current position, keep it until and unless you have another one (or until you retire, but even then, please be very sure of how you will pay your living expenses).

Let me close by saying that I fervently hope that this whole banking crisis blows over and does not result in you needing to draw upon any of the safeguards that I have laid out above. That is my most sincere wish.

But as I see things now, the chance of a banking collapse and/or dollar crisis remains unacceptably high.

Do what you need to do. Do what you believe is right, and tune out the rest.

How the Credit Markets Affect Us All

PREVIEW by Chris MartensonThursday, October 9, 2008

In this Martenson Report, I cover the importance of the credit markets to the smooth functioning of our just-in-time economy. If the credit markets fully seize up, it is not a stretch to state that most businesses and the flow of many goods will also seize up.

In fact, this has already happened, to a limited extent. Should this extend further, there are a few basic precautions that you should consider as a means of mitigating the impact of a potential banking/credit lock-up.

Okay, time for a little chat about the reasons that a credit market freeze-up has the potential to change your life in sudden and dramatic ways.

Many people mistakenly believe that at some point in the distant past we moved from a barter economy to a money-based economy. In truth, we have a credit-based economy.

In a money-based, or “cash-based,” economy, the whole thing would work a lot like your debit card. Businesses would immediately swap money for goods at the point of the transaction.

But that’s not how our system operates. Instead, when goods flow between distributors, suppliers, and retailers, they do so on the basis of credit. For example, if your local grocery chain orders additional food from their distributor, credit is what gets that transaction moving right away. The grocery store has a line of credit with the distributor, which has a line of credit with their bank, which has lines of credit with other banks, one of which has a credit arrangement with the grocery store.

Typically, businesses carry 30-60-90-day terms on cash settlement for goods and services sent/received. So the lines of credit are an important ‘lubricant’ to the process of buying and selling goods, with cash settlement coming after-the-fact and often comprising a bulk payment for numerous credit-based transactions that might have occurred over a period of time.

At the larger level, credit transactions worth trillions of dollars are occurring between importers and exporters, with municipality paychecks, between nations, in stock margin accounts, and so forth. Credit is everywhere and it is how we conduct business. Without credit, we’d need to revert to a cash-based economy (hard cash or the electronic equivalent) and the simple fact is that our financial and judicial machinery are just not set up to handle a cash-based economy. They could be, I suppose, but right now they aren’t.

So we need to ask ourselves, “What will happen if the credit markets completely freeze up?” Here’s an example from Tuesday (Oct 7th, 2008), neatly illustrating the confusion and stasis that results from a credit market seizure:

The credit crisis is spilling over into the grain industry as international buyers find themselves unable to come up with payment, forcing sellers to shoulder often substantial losses.

Before cargoes can be loaded at port, buyers typically must produce proof they are good for the money. But more deals are falling through as sellers decide they don’t trust the financial institution named in the buyer’s letter of credit, analysts said.

"There’s all kinds of stuff stacked up on docks right now that can’t be shipped because people can’t get letters of credit," said Bill Gary, president of Commodity Information Systems in Oklahoma City. "The problem is not demand, and it’s not supply because we have plenty of supply. It’s finding anyone who can come up with the credit to buy."

In the article above there are willing buyers and sellers but believable bank credit is the missing element.

Banks are essential intermediaries in a credit-based system, and the flow of goods comes to a shuddering halt without available, and, most importantly, believable credit. Sure, I suppose it is possible for a buyer to wire over the cash money to release the goods, but that type of exchange takes a different form of trust that is very likely to be in short supply during a crisis. Who would want to send off money without a system of assurances that the products will be shipped? Where there is an entire system of checks and balances erected around credit transactions, there are fewer for cash transactions.

Think of an Ebay auction where you use your credit card vs. sending off cash in an envelope. If the deal goes bad, you have more options for recourse under the credit transaction than the cash transaction. This is also true for businesses of every size.

This is why the recent decision to allow banks to “mark (all of their toxic assets) to maturity” was a bad move. While it helped the balance sheets appear to be healthier, which I am sure made some CEOs happy, it also served to make the banks’ financial positions less transparent, causing an offsetting erosion of confidence. After this move there is now less certainty about anyone’s solvency. And so our credit markets are seizing up, and grain is not being shipped from docks. On the surface this may not seem like a huge problem, but once you understand how our entire economy is predicated on a “just in time” delivery system, the problem is obvious. A couple of examples:

- Grocery stores typically only have 3-5 days of food on hand. The continuous arrival of new trucks on a daily basis is essential to keeping them supplied. Credit allows this to happen.

- The US imports 17% of its daily gasoline needs from foreign refiners. Credit allows this to happen.

Literally every single supply chain in our complicated consumer network is dependent on the smooth functioning of the credit markets. (Okay, maybe not the illegal drug market, but you get the drift.) While it is possible to switch to a cash-based scheme for normal business transactions, that process will take time, possibly years, and the credit markets are currently imploding at a rate that suggests we have only a few weeks to sort all this out.

This is what is happening behind the scenes, and this is why the Treasury Department and the Federal Reserve are operating in such a panic mode.

In a larger sense, what we are seeing is the inevitable result of a fractional reserve banking system that has burned itself out. In 2003, Alan Greenspan reduced the US interest rate to the emergency level of 1% and held it there for a year. The rest of the world’s central banks followed suit, and the rest is history.

As a result, we had the greatest expansion of debt that the world has ever seen. Credit bubbles always end in a bust, and they do not end until all of the prior excesses are wrung out of the system. For the US, this presents quite a tricky bit of landscape to navigate, because we mainly financed our excesses through foreign borrowing. Plus, we still own the world’s reserve currency. Together these facts compound the difficulty of managing a successful conclusion to the crisis.

So we are now forced to admit, at least to ourselves, that it is now possible that both the dollar and the entire fractional reserve banking system could implode.

In the case of the dollar, trillions and trillions of them are now held by foreigners. In order for the dollar to merely maintain its value internationally, foreigners must keep buying it at the same pace as before. If they continue to maintain their current dollar positions, but stop buying more, the dollar will fall. If they stop buying more and decide to unload the ones they already have, then the dollar will crash.

We have, in essence, three generations of excess spending out there in the hands of foreign nations, some of them openly hostile to the US. Our future rests upon their kindness. In the case of the banking system, it is already, obviously, in terrible shape. The entire network, in aggregate, is insolvent. The damage in several key financial stocks this week has been staggering, if not frightening.

Recalling my earlier statement about “marking to maturity,” we can see evidence of the resulting level of concern by viewing the stock price of Citigroup, which holds slightly more than $1 trillion (with a “t”) of the so-called “Level III” assets, which are equivalent to the “marked-to-maturity” assets that I spoke of earlier. Here we can see that Citigroup is rapidly approaching its recent lows, having lost all of the momentum that the “no short” rule change gave it a while back:

And here are several other major insurers that are certainly going down soon. MetLife starts the ball rolling here:

That chart, my friends, is a complete disaster. Something is very broken at MET that will require a lot of fixing. MET “…offers life insurance, annuities, automobile and homeowners insurance, retail banking and other financial services to individuals, as well as group insurance, reinsurance and retirement and savings products and services to corporations, and other institutions."

And here’s Prudential Financial. This, too, is a very ugly chart:

PRU “…offers an array of financial products and services, including life insurance, annuities, mutual funds, pension and retirement-related services and administration, investment management, real estate brokerage and relocation services, and, through a joint venture, retail securities brokerage services.”

And here’s Aegon, a major holding company offering insurance, pension, and financial services and products. This chart shows the complete breakdown of yet another gigantic company with financial tendrils that reach far and wide:

And here’s the last one, Hartford Financial Services (HIG – primarily an insurance company), slightly larger than AEG but smaller than MET:

These are all gigantic companies, each as large as Enron and each with charts indicating that utter failure is just around the corner. We can all hope that a financial rescue is in the works that will be able to fix all of this, but we’d be better off planning as if that weren’t going to happen.

What you can do about this

First, I want you to accept the possibility that the entire banking system could go into a form of financial cardiac arrest and fail to work properly. If this happens, uncertainty and fear will rule the day. Jobs will be lost, goods will grow scarce, and rumors will fly.

The most obvious impacts will be felt locally. Towns, municipalities, and states will have to navigate the loss of significant portions of their budgets. Services will be cut. Some stores and supply channels will not be able to operate, either because their cash flow got pinched and they went out of business as a result, or because their credit facilities dried up and prevented normal operations. Some goods will rapidly become scarce.

The first step in preparing yourself for this scenario is to understand why this has happened. By taking the Crash Course, you already know the mechanics of this situation and that everything that the Treasury and Fed are trying to fix (at least publicly) are merely symptoms. The cause was a 25-year-long credit binge that finally ran out of steam.

The second thing you can do is to adopt a highly defensive posture with respect to money and your basic living arrangements. Let me reiterate the basic Tier I actions that you should all have taken by now:

- Trim your expenses as far as humanly possible.

- Keep cash out of the bank. Three months’ living expenses if you can; otherwise as much as possible.

- Do you have essential medicines that you count on? If it’s possible, keep an extra supply around the house.

- When you can, keep things topped off around the home. I recommend keeping at least a three-month supply of food on hand, in case the trucks stop rolling for any reason. I know this may sound “out there” for some of you, and if this goes too far in your mind, simply ignore it. But for anybody who has even the slightest worry in this regard, when all is said and done it takes relatively little effort and no extra money to make this fear go away. I say “no extra money,” because you would eventually have bought and eaten the food anyways. Through all of human history, up until about 50 years ago, it would have been unthinkable for the average family not to know exactly where its food for the winter was located. Our modern dependence on just-in-time delivery is a very, very recent development, and one for which we may potentially pay a very high price

- Hold gold and silver, physical only. How much? That depends on how many of your US-dollar-denominated holdings you’d like to be absolutely sure do not go to zero.

And here are the Tier II actions that you should consider in preparing for a potential credit market collapse:

- Develop a sense of community and get to know the people you can count on and who will count on you.

- Don’t take on any more purely consumptive debt for any circumstances, unless you are speculating and can manage the risks. This means you should not buy a house that is a stretch, you should make the old car go a little longer, and you should not be putting anything on the old credit card that you cannot find a way to do without.

- Keep your job! I don’t care how much you hate your current position, keep it until and unless you have another one (or until you retire, but even then, please be very sure of how you will pay your living expenses).

Let me close by saying that I fervently hope that this whole banking crisis blows over and does not result in you needing to draw upon any of the safeguards that I have laid out above. That is my most sincere wish.

But as I see things now, the chance of a banking collapse and/or dollar crisis remains unacceptably high.

Do what you need to do. Do what you believe is right, and tune out the rest.

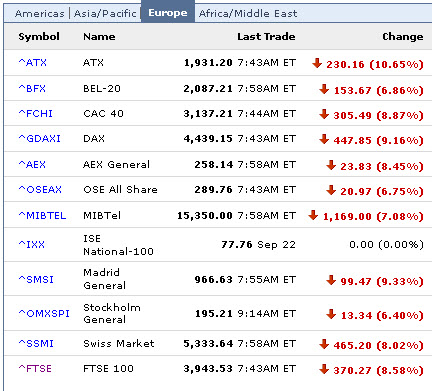

World stock markets were in meltdown mode last night. Japan was off more than 10% at one point.

So the world’s Central Banks got together and performed an emergency coordinated rate cut of 0.50% (50 basis points).

[quote]The US Federal Reserve has cut rates from 2% to 1.5% and the European Central Bank trimmed its rate from 4.25% to 3.75%.

The central banks of Canada, China, Sweden and Switzerland [and the UK] all took similar action in the coordinated move.

The unprecedented step is aimed at steadying a faltering global economy and slumping stock markets. [/quote]

Fed Funds were already at 1.25% after a stealth rate cut. This 50 basis point cut just gets us officially closer to what was already in effect. So it will not actually change the cost of money in the US at all. Not one tiny bit. Rather, this was symbolic for the US. For the EU it does represent an actual decline in the cost of money, which brings me to my next point.

Second, I cannot figure out how a rate cut does anything at this point. Yes, so money is cheaper to borrow from the Central Banks. Okay. So what?

In order for that to be effective, somebody has to want to borrow it.

Again the Central Banks are fighting the wrong fight. Where they battled liquidity, solvency was the issue.

Now, where they are battling the cost of borrowed money, they have done nothing about the desire to borrow money.

I am quite intrigued to see China on the list of involved Central Banks. This is the first time I can recall their coordinated involvement in the actions of the world banking cartel. Welcome to the club.

Japan was not involved, because they don’t have 50 basis points to cut – their monetary policy has been riding the rails right down near the zero line for years. So Japan is now saying to the rest of the world "welcome to the club!"

Despite the fact that the move was merely symbolic, the impact on the US futures was immediate and pronounced. I’ve never seen a 60 point pop in a 5 minute window before.

Bottom line: The world’s Central Banks are desperately pulling on their main lever, with fingers crossed, hoping that it will work one more time. Unfortunately, the interest rate lever cannot fix our current ills…this was merely a psychological shot in the arm, meant to let the world know that the Central Banks are taking all this seriously. A measure meant to add confidence to an economic system that operates on confidence.

Central banks cut interest rates

by Chris MartensonWorld stock markets were in meltdown mode last night. Japan was off more than 10% at one point.

So the world’s Central Banks got together and performed an emergency coordinated rate cut of 0.50% (50 basis points).

[quote]The US Federal Reserve has cut rates from 2% to 1.5% and the European Central Bank trimmed its rate from 4.25% to 3.75%.

The central banks of Canada, China, Sweden and Switzerland [and the UK] all took similar action in the coordinated move.

The unprecedented step is aimed at steadying a faltering global economy and slumping stock markets. [/quote]

Fed Funds were already at 1.25% after a stealth rate cut. This 50 basis point cut just gets us officially closer to what was already in effect. So it will not actually change the cost of money in the US at all. Not one tiny bit. Rather, this was symbolic for the US. For the EU it does represent an actual decline in the cost of money, which brings me to my next point.

Second, I cannot figure out how a rate cut does anything at this point. Yes, so money is cheaper to borrow from the Central Banks. Okay. So what?

In order for that to be effective, somebody has to want to borrow it.

Again the Central Banks are fighting the wrong fight. Where they battled liquidity, solvency was the issue.

Now, where they are battling the cost of borrowed money, they have done nothing about the desire to borrow money.

I am quite intrigued to see China on the list of involved Central Banks. This is the first time I can recall their coordinated involvement in the actions of the world banking cartel. Welcome to the club.

Japan was not involved, because they don’t have 50 basis points to cut – their monetary policy has been riding the rails right down near the zero line for years. So Japan is now saying to the rest of the world "welcome to the club!"

Despite the fact that the move was merely symbolic, the impact on the US futures was immediate and pronounced. I’ve never seen a 60 point pop in a 5 minute window before.

Bottom line: The world’s Central Banks are desperately pulling on their main lever, with fingers crossed, hoping that it will work one more time. Unfortunately, the interest rate lever cannot fix our current ills…this was merely a psychological shot in the arm, meant to let the world know that the Central Banks are taking all this seriously. A measure meant to add confidence to an economic system that operates on confidence.