Monday, December 17, 2007

Executive Summary

- A series of government bailouts attack the symptoms, utterly failing to address the root cause.

- The bailouts were for the big banks, not you.

- House prices need to decline in price by 30% to 50%, and they will.

- Trillions of dollars of losses lurk in ultra-safe pension bond funds and small Norwegian towns, as well as in some unlikely places.

- Current crisis is one of solvency, not liquidity.

Q: “Has the housing market bottomed, is it soon to bottom, or is it in the process of bottoming?”

A: No, nope, and no.

There is no means of avoiding the final collapse of a boom brought about by credit (debt) expansion. The alternative is only whether the crisis should come sooner as the result of a voluntary abandonment of further credit (debt) expansion, or later as a final and total catastrophe of the currency system involved.

~ Ludwig Von Mises

In order to get at the question of ‘Just how bad is the current housing crisis?’ we need to understand the dimensions of the problem. It is a complicated mess if one considers all the scenery in detail, but it’s startlingly simple when viewed from a distance.

![]()

The threat to our banking system is described by the extent of the mortgage losses, and those will depend on how far (and how fast) house prices fall, together with the impact of outright fraud. Below we shall explore the (very) simple reasons that explain why house prices must fall by 30% to 50%. Each one can be lumped into a category of fraud, reducing demand, or boosting supply.

- House prices rose far above income gains. Too far. They became unaffordable, and now they are in the process of correcting back to affordable levels. What goes up must come down. Simple as that.

- Mortgage lending standards are tightening up, leading to fewer people qualifying for loans. Fewer qualified buyers means demand will drop and prices will fall. Simple as that.

- From 2000 to 2007, regulatory oversight of lending practices was so lax that there was effectively none. This means that lots of fraud was committed (a fantastic summary of types of real estate fraud can be found here), and an even larger pile of bad loans were made to people who will never be able to pay them back. That money is gone, gone, gone, and somebody is going to have to eat those losses. Simple as that.

- More than one out of every four homes sold in 2005 and 2006 were sold to speculators, and now house prices are at or below 2005 levels. This means that the speculators’ investments are wiped out (and then some, considering transaction costs). Speculator demand is gone, and will not return for many years. Less demand equals lower prices. Simple as that.

- Developers overbuilt the national housing stock by a very large amount, in part to meet the false speculator demand; I calculate somewhere in the vicinity of two to three million excess units. We have too much housing stock, and it will be a minimum of three years before population gains naturally work it off. All things housing-related will be in recession until that oversupply is worked off. Simple as that.

- Even though the subprime foreclosure crisis is much closer to the beginning than the end, already hundreds of billions of dollars of losses have been recorded by small towns in Norway, in state and municipal investment funds, and by institutional money market funds. While big banks have managed to stuff all these investment channels with dodgy mortgage paper, they themselves remain as exposed to real estate loans as they’ve ever been. Truly, there is no historical precedent to inform us to how bad this could get. I estimate somewhere between $1 trillion and $2 trillion in losses, which means that the entire capital of the entire US banking system could be wiped out. This is an issue of solvency, not liquidity, and therefore this is a major crisis that goes far beyond the official actions and statements to date. Simple as that.

- In summary, real estate supply, demand, and price are severely out of whack and can only be fixed by a significant decline in prices, which means that a whole lot of individuals and financial institutions are in trouble as a consequence. It all adds up to one simple conclusion: Banks, pensions, hedge funds, and money market funds will all have to dispose of a whole lot of bad paper. Possibly up to $2 trillion dollars worth, if my calculations are correct, meaning that the potential exists for the entire capital of the US banking system to be wiped out.

Now you have all the information you need to understand why there really are no policy fixes to this mess (e.g. ‘freezing interest rates’), only an inevitable date with lower house prices. If you care to continue, below I provide my supporting data for the above statements.

From a purely logical standpoint, house prices need to fall to match those at the start of the bubble in 2000. Why? Because otherwise we have to believe in The Free Lunch. For The Free Lunch to be true, it must be possible for a person to buy a house, do nothing except sit on a couch drinking beer for the next 5 years, and get rich in the process. Examining 70 past examples of asset bubbles, we find that The Free Lunch has never worked before. It’s not going to work out this time, either.

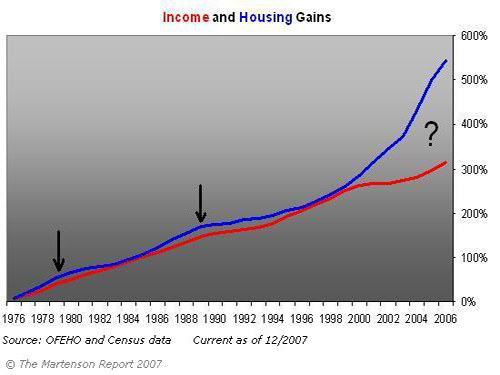

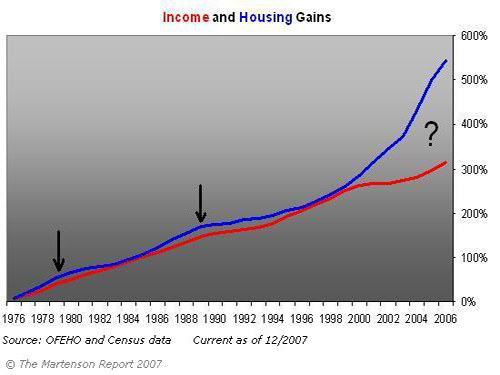

To illustrate, I put together the chart below by combining data from two government sources, the Census Bureau for income and the OFHEO for housing price gains.

What is immediately obvious is that house prices and income gains have historically tracked each other very, very closely through the entire data series until about 2000, where house prices pull significantly away from income gains. I have marked two historical housing bubbles (1979 and 1989) with arrows, noteworthy because they were well supported by income gains and therefore seem insignificant when viewed on this graph. But that in itself is noteworthy, because, as both homebuilders and house sellers during those periods can attest, it means that even a very slight departure between the blue and the red lines can be quite painful. It also means that we have no historical precedent for the territory in which we currently find ourselves.

So, onto the primary question: “What would be required to bring house prices and income gains back in line?”

The answer to that is either:

- An income gain of 51%

- A decline in house prices of 34%

Of the two, income gains or house price declines, which seems more likely? Before you answer that, you should know that the average income gain over the past 6 years has been 2.3% per year (not inflation-adjusted). At that rate it would take 21 years, or until 2028, to close the gap. In the meantime, house prices would have to remain frozen at today’s prices. In a normal world, we would see a bit of both, with house prices falling and incomes rising to meet somewhere down the road.

However, I expect house prices to do most of the heavy lifting, and I am expecting a decline of even more than 34%, possibly as much as 50%, because of the correlated job losses that will result from the housing wipeout. An outsized proportion of the meager job gains recorded since the recession of 2001 were in some way linked to housing. The ripple effect of job losses will extend far beyond realtors and mortgage brokers, and into window manufacturing, lumber, plumbing fixtures, nail salons, BMW detailing services, and so forth.

My calculations are therefore in rough alignment with those at economy.com:

NEW YORK (Reuters) – Housing markets from Punta Gorda, Florida, to Stockton, California, will crash and suffer price drops of more than 30 percent before the housing crisis is over, a report from Moody’s Economy.com said on Thursday.

On a national level, the housing market recession will continue through early 2009, said the report, co-authored by Mark Zandi, chief economist, and Celia Chen, director of housing economics.

At this particular moment in time, banks are about as heavily exposed to mortgages (as a total percent of assets) as they have ever been. Further, banks are holding an enormous quantity of commercial real estate loans, especially in the rah-rah areas such as Florida, the Southwest, and in California. The FDIC reported last year that more than 50% of all the banks in the southeast and west regions had exposure to commercial real estate loans that exceeded their total capital by 300% or more. Holy smokes!

Here’s how it happens. As the housing bubble takes off, people get into a buying frenzy, while builders get into a building frenzy. Soon enough, the commercial builders get excited and say to themselves “Saaaaay, would you lookit all these houses going up? We better build a few more malls and condos out this way!” They then go to a local or regional bank, who agrees that there’s no possible downside to building more shopping areas and condos, and so they loan huge amounts of money to these developers. When the inevitable bust comes, everybody acts surprised, and the banks go to the FDIC for a bailout. At least, that’s how it usually works. This time, because the amount of excessive building was so over the top and the banks were so unfavorably leveraged, I fully expect the FDIC to be inadequate for the job, which means Congress will have to get involved.

To put it in the simplest of terms, the total amount of bank capital in the entire country is a little over $1.1 trillion, while more than $11 trillion in real estate loans exist, meaning that a 10% to 15% loss on those loans would translate into the complete bankruptcy of the US banking system. What this all means is that we have a crisis of solvency, not liquidity. Currently the Federal Reserve has teamed up with European central banks to provide vast new sources of liquidity (unlimited, really) to the banking system. That is, banks can trade in their piles of dodgy loans for cash for a specified period of time. This gives banks access to cash. However, as currently structured, they have to buy those dodgy loans back at par, at some point in the future. If those loans are bad (which they are), then this maneuver by the Fed simply won’t work. Instead, we need wipe those bad loans out, which means we will lose a financial intuition or two (or thirty) along the way.

It is against this relatively simple backdrop of overly expensive, overbuilt housing that the government recently launched an awful, poorly conceived and named subprime bailout plan named the New Hope Alliance. “Hope?” Well, I suppose since ‘hope’ is what got us into this mess, it makes sense that the government might choose to use ‘hope’ to get us back out of it. “Hope” is not a sound strategy, which makes it a natural fit for the current housing crisis.

Since this new plan of Hope will not prevent house prices from falling, it is pretty much dead on arrival, at least as far as actually helping to solve the primary problem. The primary problem is how a lack of housing affordability will lead to a decline in prices, as brilliantly captured by this industry insider:

One final thought. How can any of this get repaired unless home values stabilize? And how will that happen? In Northern California, a household income of $90,000 per year could legitimately pay the minimum monthly payment on an Option ARM on a million home for the past several years. Most Option ARMs allowed zero to 5% down. Therefore, given the average income of the Bay Area, most families could buy that million dollar home. A home seller had a vast pool of available buyers.

Now, with all the exotic programs gone, a household income of $175,000 is needed to buy that same home, which is about 10% of the Bay Area households. And inventories are up 500%. So, in a nutshell, we have 90% fewer qualified buyers for five times the number of homes. To get housing moving again in Northern California, either all the exotic programs must come back, everyone must get a 100% raise, or home prices have to fall 50%. None, except the last, sound remotely possible.

Wow. A tenfold reduction in buyers and a fivefold increase in house supply. There is only one way for that to resolve, and that is through reduced prices.

As presented, the purpose of the program of Hope was to help prevent or delay foreclosures – as if they were the problem. Unfortunately, foreclosures are merely the symptom. The cause is the fact that people bought overpriced houses they couldn’t afford, while hoping that rising house prices would provide a ready source of cashout mortgage money. House prices are no longer rising, they are falling. That is the root of the current crisis, and this most recent government fix does absolutely nothing about it. So we can score the plan a zero on that front. Where the New Hope Alliance really breaks down and becomes a solid negative, though, is in how it undermines confidence in the sanctity of US contract law.

Dec. 7 (Bloomberg) — President George W. Bush’s plan to freeze interest rates on some subprime mortgages may prove to be a cure that breeds another disease.

“If the government goes in and changes contracts it will definitely have a chilling effect on the securitization of mortgages,” said Milton Ezrati, senior economist and market strategist at Lord Abbett & Co. in Jersey City, New Jersey, which oversees $120 billion in assets.

“When the government comes in and says you have contracted to have this arrangement and you can no longer have it, I think it opens the door for lawsuits.”

What’s being said here is that enforceable contracts are a vital component of the US financial industry. Heck, of the entire US way of life, since it is the trust foreigners place in our ‘system’ that gives them the confidence to loan us back the money we spent on their products. Without the trust that a given contract will be collectible, then those contracts either get written at a much higher price to compensate for the risk of not being paid, or they do not get written at all. So if part of the subprime crisis is reduced house prices resulting from reduced demand, would we expect a serious disturbance in mortgage contract enforceability to result in more or fewer mortgages written? Who will be able to afford significantly higher mortgage payments? Who will issue them? Who would buy them and hold them?

This is an important concept, because a huge prop to our economy over the past decade has been the flood of foreign funds that allowed us to enjoy low interest rates even as our trade deficit plumbed new depths. Part of the reason foreigners felt comfortable, if not confident, investing in the US, is that our contract laws and supporting legal infrastructure are exceptionally strong in protecting investors’ claims. Foreign investors bought many packaged mortgage products from Wall Street banks at a price based on expected returns that included future rate adjustments. That’s now at risk. This would be no different than your boss telling you that next year’s 5% raise, which you are counting on and have in writing, is actually going to be 0% – but could you please loan him another few hundred bucks?

So what was the purpose of the New Hope deal? Simple. It’s meant to bail out big banks and mortgage companies who simply do not wish to recognize the actual value of the mortgages they hold at current market prices. When houses enter foreclosure and then get sold, a price discovery event happens that ‘hits the books’ of the financial institution involved.

Here’s the best explanation of the week, courtesy of the San Francisco Gate:

Now, just unveiled Thursday, comes the “freeze,” the brainchild of Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson. It sounds good: For five years, mortgage lenders will freeze interest rates on a limited number of “teaser” subprime loans. Other homeowners facing foreclosure will be offered assistance from the Federal Housing Administration.

But unfortunately, the “freeze” is just another fraud – and like the other bailout proposals, it has nothing to do with U.S. house prices, with “working families,” keeping people in their homes or any of that nonsense.

The sole goal of the freeze is to prevent owners of mortgage-backed securities, many of them foreigners, from suing U.S. banks and forcing them to buy back worthless mortgage securities at face value – right now almost 10 times their market worth.

The ticking time bomb in the U.S. banking system is not resetting subprime mortgage rates. The real problem is the contractual ability of investors in mortgage bonds to require banks to buy back the loans at face value if there was fraud in the origination process.

And, to be sure, fraud is everywhere. It’s in the loan application documents, and it’s in the appraisals. There are e-mails and memos floating around showing that many people in banks, investment banks and appraisal companies – all the way up to senior management – knew about it.

However, this was actually the third bailout/remedy by the government. There were already two past bailouts that were simply not well publicized, and those are the ones to which you should be paying attention, because they involve vast gobs of public money.

The first was this eye-popping advance by the Federal Home Loan Bank system (FHLB) to the overall mortgage market in October:

NEW YORK (Fortune) — As the credit crunch hit hard in the third quarter, most banks were forced to cut back their lending. But one group of banks increased lending by an incredible $182 billion. Who were these deep-pocketed lenders — and are they capable of handling such a large rise in loans, especially at a time when credit markets are unsettled and mortgage defaults on the rise?

The lenders in question were the 12 Federal Home Loan Banks, set up under a government charter during the Great Depression to provide support to the housing market by advancing funds to over 8000 member banks that make mortgages. In the third quarter, loans to member banks, also called ‘advances,’ totaled $822 billion, a 28% leap from $640 billion at the end of June.

This is a staggering amount of mortgage-buying activity. Where did this $182 billion come from? Did the FHLB just happen to have nearly $200 billion lying around? If not, how was it that the FHLB was able to find buyers for mortgage paper at a time when the mortgage markets were more or less frozen? What sorts of mortgages were purchased? Were they high grade or the subbiest of the subprime? In point of fact, it is a bailout, plain and simple. It is an egregious use of public monies that was not voted on, but is guaranteed, by the public. But the FHLB fiduciary stewards did not stop there. They went further, by advancing a stunning $51 billion to Countrywide Financial Corp, recently voted as most likely to fail by its classmates. How bad does this move smell? Bad enough for a US Senator to notice.

In a letter to the regulator of the Federal Home Loan Bank system, Sen. Charles Schumer said Countrywide, the largest U.S. mortgage lender, may be abusing the program.

At the end of September, Countrywide had borrowed $51.1 billion from the Federal Home Loan Bank system — a government-sponsored program.

“Countrywide is treating the Federal Home Loan Bank system like its personal ATM,” Schumer, a New York Democrat who heads the housing panel of the Senate Banking Committee, said in the letter. “At a time when Countrywide’s mortgage portfolio is deteriorating drastically, FHLB’s exposure to Countrywide poses an unreasonable risk.”

So what we have here is a case where the fiscal and monetary authorities are desperately shoving enormous amounts of money (and new policy) into a very stressed and ultimately unsavable situation. On a personal level, this bothers me a great deal. Partly because I have been prudent and saved and rented while waiting for the silliness to end, yet the very first response of my government is to punish me and reward the imprudent. But mainly because big bailouts doubly punish us all; first, by the inevitable inflation that results, and second, because our future options will be diminished by debt.

What needs to happen is very clear. The bad debts need to be wiped out. The mal-investments need to be written off.

So now that we know this thing is going to implode, the only relevant part left is to ask the questions, ‘How am I exposed, and how can I avoid having the bag passed to me?’

Here I will revert to my past recommendations:

- Get out of debt.

- Be very careful about where you keep your money. Already several high profile money market funds have suffered losses and closed down, returning less than the deposit amount to their clients. Expect this to get worse.

- The dollar is in a precarious situation, especially if the Fed begins buying up bad debt for paper money in a big way. Gold. Silver. Top off your oil tank at home.

- Be aware that pensions, municipal investment accounts, and even your bank are all highly likely to be exposed to the leveraged losses that are now upon us. If you are exposed here, figure out how not to be.

- If you are a citizen of a country whose central bank insists on bailing out the monied elite (big banks) with your current and/or future tax dollars, use every possible avenue available to legally apply pressure upon your political representatives to prevent this from happening.

Now, go back to the top and re-read the quote by Ludwig Von Mises. It neatly describes everything you need to know. The preceding 20 paragraphs were my way of illustrating that there will be no voluntary abandonment of credit expansion. In fact, the data shows that our fiscal and monetary authorities are fighting that possible outcome tooth and nail. That leaves the dollar exposed to the risk of losing its reserve currency status as it heads towards international pariah status. Not that there’s anything wrong with that…unless you think we might, someday, need to import oil, or something made out of plastic, or electronics, or underwear, or …

Housing – Simple As That

PREVIEW by Chris MartensonMonday, December 17, 2007

Executive Summary

- A series of government bailouts attack the symptoms, utterly failing to address the root cause.

- The bailouts were for the big banks, not you.

- House prices need to decline in price by 30% to 50%, and they will.

- Trillions of dollars of losses lurk in ultra-safe pension bond funds and small Norwegian towns, as well as in some unlikely places.

- Current crisis is one of solvency, not liquidity.

Q: “Has the housing market bottomed, is it soon to bottom, or is it in the process of bottoming?”

A: No, nope, and no.

There is no means of avoiding the final collapse of a boom brought about by credit (debt) expansion. The alternative is only whether the crisis should come sooner as the result of a voluntary abandonment of further credit (debt) expansion, or later as a final and total catastrophe of the currency system involved.

~ Ludwig Von Mises

In order to get at the question of ‘Just how bad is the current housing crisis?’ we need to understand the dimensions of the problem. It is a complicated mess if one considers all the scenery in detail, but it’s startlingly simple when viewed from a distance.

![]()

The threat to our banking system is described by the extent of the mortgage losses, and those will depend on how far (and how fast) house prices fall, together with the impact of outright fraud. Below we shall explore the (very) simple reasons that explain why house prices must fall by 30% to 50%. Each one can be lumped into a category of fraud, reducing demand, or boosting supply.

- House prices rose far above income gains. Too far. They became unaffordable, and now they are in the process of correcting back to affordable levels. What goes up must come down. Simple as that.

- Mortgage lending standards are tightening up, leading to fewer people qualifying for loans. Fewer qualified buyers means demand will drop and prices will fall. Simple as that.

- From 2000 to 2007, regulatory oversight of lending practices was so lax that there was effectively none. This means that lots of fraud was committed (a fantastic summary of types of real estate fraud can be found here), and an even larger pile of bad loans were made to people who will never be able to pay them back. That money is gone, gone, gone, and somebody is going to have to eat those losses. Simple as that.

- More than one out of every four homes sold in 2005 and 2006 were sold to speculators, and now house prices are at or below 2005 levels. This means that the speculators’ investments are wiped out (and then some, considering transaction costs). Speculator demand is gone, and will not return for many years. Less demand equals lower prices. Simple as that.

- Developers overbuilt the national housing stock by a very large amount, in part to meet the false speculator demand; I calculate somewhere in the vicinity of two to three million excess units. We have too much housing stock, and it will be a minimum of three years before population gains naturally work it off. All things housing-related will be in recession until that oversupply is worked off. Simple as that.

- Even though the subprime foreclosure crisis is much closer to the beginning than the end, already hundreds of billions of dollars of losses have been recorded by small towns in Norway, in state and municipal investment funds, and by institutional money market funds. While big banks have managed to stuff all these investment channels with dodgy mortgage paper, they themselves remain as exposed to real estate loans as they’ve ever been. Truly, there is no historical precedent to inform us to how bad this could get. I estimate somewhere between $1 trillion and $2 trillion in losses, which means that the entire capital of the entire US banking system could be wiped out. This is an issue of solvency, not liquidity, and therefore this is a major crisis that goes far beyond the official actions and statements to date. Simple as that.

- In summary, real estate supply, demand, and price are severely out of whack and can only be fixed by a significant decline in prices, which means that a whole lot of individuals and financial institutions are in trouble as a consequence. It all adds up to one simple conclusion: Banks, pensions, hedge funds, and money market funds will all have to dispose of a whole lot of bad paper. Possibly up to $2 trillion dollars worth, if my calculations are correct, meaning that the potential exists for the entire capital of the US banking system to be wiped out.

Now you have all the information you need to understand why there really are no policy fixes to this mess (e.g. ‘freezing interest rates’), only an inevitable date with lower house prices. If you care to continue, below I provide my supporting data for the above statements.

From a purely logical standpoint, house prices need to fall to match those at the start of the bubble in 2000. Why? Because otherwise we have to believe in The Free Lunch. For The Free Lunch to be true, it must be possible for a person to buy a house, do nothing except sit on a couch drinking beer for the next 5 years, and get rich in the process. Examining 70 past examples of asset bubbles, we find that The Free Lunch has never worked before. It’s not going to work out this time, either.

To illustrate, I put together the chart below by combining data from two government sources, the Census Bureau for income and the OFHEO for housing price gains.

What is immediately obvious is that house prices and income gains have historically tracked each other very, very closely through the entire data series until about 2000, where house prices pull significantly away from income gains. I have marked two historical housing bubbles (1979 and 1989) with arrows, noteworthy because they were well supported by income gains and therefore seem insignificant when viewed on this graph. But that in itself is noteworthy, because, as both homebuilders and house sellers during those periods can attest, it means that even a very slight departure between the blue and the red lines can be quite painful. It also means that we have no historical precedent for the territory in which we currently find ourselves.

So, onto the primary question: “What would be required to bring house prices and income gains back in line?”

The answer to that is either:

- An income gain of 51%

- A decline in house prices of 34%

Of the two, income gains or house price declines, which seems more likely? Before you answer that, you should know that the average income gain over the past 6 years has been 2.3% per year (not inflation-adjusted). At that rate it would take 21 years, or until 2028, to close the gap. In the meantime, house prices would have to remain frozen at today’s prices. In a normal world, we would see a bit of both, with house prices falling and incomes rising to meet somewhere down the road.

However, I expect house prices to do most of the heavy lifting, and I am expecting a decline of even more than 34%, possibly as much as 50%, because of the correlated job losses that will result from the housing wipeout. An outsized proportion of the meager job gains recorded since the recession of 2001 were in some way linked to housing. The ripple effect of job losses will extend far beyond realtors and mortgage brokers, and into window manufacturing, lumber, plumbing fixtures, nail salons, BMW detailing services, and so forth.

My calculations are therefore in rough alignment with those at economy.com:

NEW YORK (Reuters) – Housing markets from Punta Gorda, Florida, to Stockton, California, will crash and suffer price drops of more than 30 percent before the housing crisis is over, a report from Moody’s Economy.com said on Thursday.

On a national level, the housing market recession will continue through early 2009, said the report, co-authored by Mark Zandi, chief economist, and Celia Chen, director of housing economics.

At this particular moment in time, banks are about as heavily exposed to mortgages (as a total percent of assets) as they have ever been. Further, banks are holding an enormous quantity of commercial real estate loans, especially in the rah-rah areas such as Florida, the Southwest, and in California. The FDIC reported last year that more than 50% of all the banks in the southeast and west regions had exposure to commercial real estate loans that exceeded their total capital by 300% or more. Holy smokes!

Here’s how it happens. As the housing bubble takes off, people get into a buying frenzy, while builders get into a building frenzy. Soon enough, the commercial builders get excited and say to themselves “Saaaaay, would you lookit all these houses going up? We better build a few more malls and condos out this way!” They then go to a local or regional bank, who agrees that there’s no possible downside to building more shopping areas and condos, and so they loan huge amounts of money to these developers. When the inevitable bust comes, everybody acts surprised, and the banks go to the FDIC for a bailout. At least, that’s how it usually works. This time, because the amount of excessive building was so over the top and the banks were so unfavorably leveraged, I fully expect the FDIC to be inadequate for the job, which means Congress will have to get involved.

To put it in the simplest of terms, the total amount of bank capital in the entire country is a little over $1.1 trillion, while more than $11 trillion in real estate loans exist, meaning that a 10% to 15% loss on those loans would translate into the complete bankruptcy of the US banking system. What this all means is that we have a crisis of solvency, not liquidity. Currently the Federal Reserve has teamed up with European central banks to provide vast new sources of liquidity (unlimited, really) to the banking system. That is, banks can trade in their piles of dodgy loans for cash for a specified period of time. This gives banks access to cash. However, as currently structured, they have to buy those dodgy loans back at par, at some point in the future. If those loans are bad (which they are), then this maneuver by the Fed simply won’t work. Instead, we need wipe those bad loans out, which means we will lose a financial intuition or two (or thirty) along the way.

It is against this relatively simple backdrop of overly expensive, overbuilt housing that the government recently launched an awful, poorly conceived and named subprime bailout plan named the New Hope Alliance. “Hope?” Well, I suppose since ‘hope’ is what got us into this mess, it makes sense that the government might choose to use ‘hope’ to get us back out of it. “Hope” is not a sound strategy, which makes it a natural fit for the current housing crisis.

Since this new plan of Hope will not prevent house prices from falling, it is pretty much dead on arrival, at least as far as actually helping to solve the primary problem. The primary problem is how a lack of housing affordability will lead to a decline in prices, as brilliantly captured by this industry insider:

One final thought. How can any of this get repaired unless home values stabilize? And how will that happen? In Northern California, a household income of $90,000 per year could legitimately pay the minimum monthly payment on an Option ARM on a million home for the past several years. Most Option ARMs allowed zero to 5% down. Therefore, given the average income of the Bay Area, most families could buy that million dollar home. A home seller had a vast pool of available buyers.

Now, with all the exotic programs gone, a household income of $175,000 is needed to buy that same home, which is about 10% of the Bay Area households. And inventories are up 500%. So, in a nutshell, we have 90% fewer qualified buyers for five times the number of homes. To get housing moving again in Northern California, either all the exotic programs must come back, everyone must get a 100% raise, or home prices have to fall 50%. None, except the last, sound remotely possible.

Wow. A tenfold reduction in buyers and a fivefold increase in house supply. There is only one way for that to resolve, and that is through reduced prices.

As presented, the purpose of the program of Hope was to help prevent or delay foreclosures – as if they were the problem. Unfortunately, foreclosures are merely the symptom. The cause is the fact that people bought overpriced houses they couldn’t afford, while hoping that rising house prices would provide a ready source of cashout mortgage money. House prices are no longer rising, they are falling. That is the root of the current crisis, and this most recent government fix does absolutely nothing about it. So we can score the plan a zero on that front. Where the New Hope Alliance really breaks down and becomes a solid negative, though, is in how it undermines confidence in the sanctity of US contract law.

Dec. 7 (Bloomberg) — President George W. Bush’s plan to freeze interest rates on some subprime mortgages may prove to be a cure that breeds another disease.

“If the government goes in and changes contracts it will definitely have a chilling effect on the securitization of mortgages,” said Milton Ezrati, senior economist and market strategist at Lord Abbett & Co. in Jersey City, New Jersey, which oversees $120 billion in assets.

“When the government comes in and says you have contracted to have this arrangement and you can no longer have it, I think it opens the door for lawsuits.”

What’s being said here is that enforceable contracts are a vital component of the US financial industry. Heck, of the entire US way of life, since it is the trust foreigners place in our ‘system’ that gives them the confidence to loan us back the money we spent on their products. Without the trust that a given contract will be collectible, then those contracts either get written at a much higher price to compensate for the risk of not being paid, or they do not get written at all. So if part of the subprime crisis is reduced house prices resulting from reduced demand, would we expect a serious disturbance in mortgage contract enforceability to result in more or fewer mortgages written? Who will be able to afford significantly higher mortgage payments? Who will issue them? Who would buy them and hold them?

This is an important concept, because a huge prop to our economy over the past decade has been the flood of foreign funds that allowed us to enjoy low interest rates even as our trade deficit plumbed new depths. Part of the reason foreigners felt comfortable, if not confident, investing in the US, is that our contract laws and supporting legal infrastructure are exceptionally strong in protecting investors’ claims. Foreign investors bought many packaged mortgage products from Wall Street banks at a price based on expected returns that included future rate adjustments. That’s now at risk. This would be no different than your boss telling you that next year’s 5% raise, which you are counting on and have in writing, is actually going to be 0% – but could you please loan him another few hundred bucks?

So what was the purpose of the New Hope deal? Simple. It’s meant to bail out big banks and mortgage companies who simply do not wish to recognize the actual value of the mortgages they hold at current market prices. When houses enter foreclosure and then get sold, a price discovery event happens that ‘hits the books’ of the financial institution involved.

Here’s the best explanation of the week, courtesy of the San Francisco Gate:

Now, just unveiled Thursday, comes the “freeze,” the brainchild of Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson. It sounds good: For five years, mortgage lenders will freeze interest rates on a limited number of “teaser” subprime loans. Other homeowners facing foreclosure will be offered assistance from the Federal Housing Administration.

But unfortunately, the “freeze” is just another fraud – and like the other bailout proposals, it has nothing to do with U.S. house prices, with “working families,” keeping people in their homes or any of that nonsense.

The sole goal of the freeze is to prevent owners of mortgage-backed securities, many of them foreigners, from suing U.S. banks and forcing them to buy back worthless mortgage securities at face value – right now almost 10 times their market worth.

The ticking time bomb in the U.S. banking system is not resetting subprime mortgage rates. The real problem is the contractual ability of investors in mortgage bonds to require banks to buy back the loans at face value if there was fraud in the origination process.

And, to be sure, fraud is everywhere. It’s in the loan application documents, and it’s in the appraisals. There are e-mails and memos floating around showing that many people in banks, investment banks and appraisal companies – all the way up to senior management – knew about it.

However, this was actually the third bailout/remedy by the government. There were already two past bailouts that were simply not well publicized, and those are the ones to which you should be paying attention, because they involve vast gobs of public money.

The first was this eye-popping advance by the Federal Home Loan Bank system (FHLB) to the overall mortgage market in October:

NEW YORK (Fortune) — As the credit crunch hit hard in the third quarter, most banks were forced to cut back their lending. But one group of banks increased lending by an incredible $182 billion. Who were these deep-pocketed lenders — and are they capable of handling such a large rise in loans, especially at a time when credit markets are unsettled and mortgage defaults on the rise?

The lenders in question were the 12 Federal Home Loan Banks, set up under a government charter during the Great Depression to provide support to the housing market by advancing funds to over 8000 member banks that make mortgages. In the third quarter, loans to member banks, also called ‘advances,’ totaled $822 billion, a 28% leap from $640 billion at the end of June.

This is a staggering amount of mortgage-buying activity. Where did this $182 billion come from? Did the FHLB just happen to have nearly $200 billion lying around? If not, how was it that the FHLB was able to find buyers for mortgage paper at a time when the mortgage markets were more or less frozen? What sorts of mortgages were purchased? Were they high grade or the subbiest of the subprime? In point of fact, it is a bailout, plain and simple. It is an egregious use of public monies that was not voted on, but is guaranteed, by the public. But the FHLB fiduciary stewards did not stop there. They went further, by advancing a stunning $51 billion to Countrywide Financial Corp, recently voted as most likely to fail by its classmates. How bad does this move smell? Bad enough for a US Senator to notice.

In a letter to the regulator of the Federal Home Loan Bank system, Sen. Charles Schumer said Countrywide, the largest U.S. mortgage lender, may be abusing the program.

At the end of September, Countrywide had borrowed $51.1 billion from the Federal Home Loan Bank system — a government-sponsored program.

“Countrywide is treating the Federal Home Loan Bank system like its personal ATM,” Schumer, a New York Democrat who heads the housing panel of the Senate Banking Committee, said in the letter. “At a time when Countrywide’s mortgage portfolio is deteriorating drastically, FHLB’s exposure to Countrywide poses an unreasonable risk.”

So what we have here is a case where the fiscal and monetary authorities are desperately shoving enormous amounts of money (and new policy) into a very stressed and ultimately unsavable situation. On a personal level, this bothers me a great deal. Partly because I have been prudent and saved and rented while waiting for the silliness to end, yet the very first response of my government is to punish me and reward the imprudent. But mainly because big bailouts doubly punish us all; first, by the inevitable inflation that results, and second, because our future options will be diminished by debt.

What needs to happen is very clear. The bad debts need to be wiped out. The mal-investments need to be written off.

So now that we know this thing is going to implode, the only relevant part left is to ask the questions, ‘How am I exposed, and how can I avoid having the bag passed to me?’

Here I will revert to my past recommendations:

- Get out of debt.

- Be very careful about where you keep your money. Already several high profile money market funds have suffered losses and closed down, returning less than the deposit amount to their clients. Expect this to get worse.

- The dollar is in a precarious situation, especially if the Fed begins buying up bad debt for paper money in a big way. Gold. Silver. Top off your oil tank at home.

- Be aware that pensions, municipal investment accounts, and even your bank are all highly likely to be exposed to the leveraged losses that are now upon us. If you are exposed here, figure out how not to be.

- If you are a citizen of a country whose central bank insists on bailing out the monied elite (big banks) with your current and/or future tax dollars, use every possible avenue available to legally apply pressure upon your political representatives to prevent this from happening.

Now, go back to the top and re-read the quote by Ludwig Von Mises. It neatly describes everything you need to know. The preceding 20 paragraphs were my way of illustrating that there will be no voluntary abandonment of credit expansion. In fact, the data shows that our fiscal and monetary authorities are fighting that possible outcome tooth and nail. That leaves the dollar exposed to the risk of losing its reserve currency status as it heads towards international pariah status. Not that there’s anything wrong with that…unless you think we might, someday, need to import oil, or something made out of plastic, or electronics, or underwear, or …