Wednesday, June 18, 2008

Executive Summary

- Relatively benign stock market index performance is masking severe financial weakness

- Judging by their stock charts, several good-sized banks might file for bankruptcy soon

- Financial market liquidity supplied by the Fed is at odds with their words that "credit market conditions are improving"

- The assets of the banks under duress are many, many multiples of total FDIC assets

"Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain!" barks the booming voice.

Unfortunately for the dumpy, balding ‘wizard,’ the curtain has already been removed and he’s been spotted.

The first two weeks of June (2008) have been all about knowing where to look. Let’s peel back the curtain.

Let me begin with a personal story. One of my main trading accounts was with a company called Lind-Waldock, a very reputable, stable, old company that got bought out by fast-flying Refco. All seemed well for the first few months, I had the same broker at the other end of the phone and I noticed no difference in my trading experience. But I was wary of Refco, so I kept a live stock chart up on my computer monitor, which I kept a close eye on. One day, the stock price of Refco took a stomach-wrenching dive, losing nearly 20% in a single hour. I immediately called my broker and shifted my funds out of that company that very day. I even got a call from the head of the division asking me to remain, insisting that all was well, and explaining that the stock was falling on the basis of unsubstantiated and certainly untrue rumors. It turns out that the rumors were true; Refco was involved in some shenanigans and had clumsily tried to hide billions in losses by stuffing them in an off-shore subsidiary. Refco was actually insolvent and ultimately went bankrupt. And it was also true that my money would have been safe even had I not moved it, but my position on these matters is to bring the money home and ask the detailed questions later.

Below you will see many examples of stock price performance that would cause me personally to remove my money to a safer location and save the questions for later.

After the dangerous downdraft in the dollar and the stock market seen on Friday the 6th of June, the Federal Reserve and their brethren in Europe, the ECB, were all over the airwaves beginning Sunday the 8th in an attempt to prevent the markets from selling off any further. Judging by the headline stock index performance, they did pretty well, as the indexes closed more or less unchanged for the week. However, if we peek behind the curtains, we see something very different.

I want to focus on the issue of banks and bank solvency. Actually, I want to broaden this definition to include what are termed "financial institutions," which include mortgage brokers and commercial lending institutions. Why? Because we are now a financial economy. Measured in dollars, our economy has much more activity in the business of moving money around than it does in the manufacturing real goods.

It used to be said that "as goes GM, so goes the US," meaning that the economic health of the country could be measured by the activity of its (formerly) largest manufacturer. Now it might be said that "as goes JP Morgan, so goes the country."

Here are the warning signs that major and probably systemic financial distress remains threaded throughout our economy like termite tunnels in a load-bearing beam.

The Fed’s words and actions are not aligned

Bernanke recently said that the risk the economy has entered a substantial downturn "appears to have diminished over the past month or so," while Alan Greenspan said that financial markets have shown a "pronounced turnaround" since March. Which leads us to the recent inflation-fighting words of Bernanke, who said that the Fed would "strongly resist" expectations that inflation will accelerate, hinting at the possibility that interest rates will be raised. Of course, all of these are simply words. What are the actions?

Since you and I know that inflation is caused by too much money lent too cheaply, we’ll spend less time listening to words and more time looking at the monetary data. In other words, let’s pay attention to what they are doing, not what they are saying.

Through a combination of Federal Reserve and Treasury actions, the total amount of liquidity that has been injected into the banking system has advanced over $40 billion in the last 10 days, smashing to a new all-time record of more than $307 billion dollars. If the worst was behind us and inflation was a real concern, this would not have happened. The actions here tell us that the fear of whatever is ailing the banking system vastly outweighs any concerns about inflation.

Further, short-term interest rates are set at 2.0%, which is a full two percent below the rate of inflation. What do you get when you combine negative real interest rates with extremely loose monetary policy? Inflation.

And finally, here’s a chart of the money supply of this nation. If this was a roller coaster ride, you’d be pressed back in your seat staring at the sky – not unlike oil, grains, and other basic commodities.

So there you have it: On the one side, record amounts of liquidity, deeply negative real interest rates, and a near-vertical rise in monetary aggregates. And on the other side, words.

So there you have it: On the one side, record amounts of liquidity, deeply negative real interest rates, and a near-vertical rise in monetary aggregates. And on the other side, words.

Bank and financial stocks under attack

When I want to know how a company is doing, I turn to a chart of its stock price. Long before the headlines are written of a company’s undoing, the stock price has already told the tale. The story currently being told by the stock price of several mid-sized banks, mortgage companies, and bond insurers is nothing short of a disaster in the making.

You need to be paying attention to these next few charts. Remember, Bernanke and Greenspan want you to think that the worst is behind us and that things turned around in March.

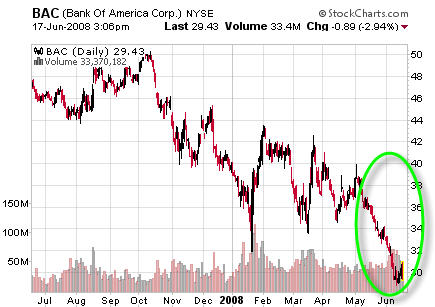

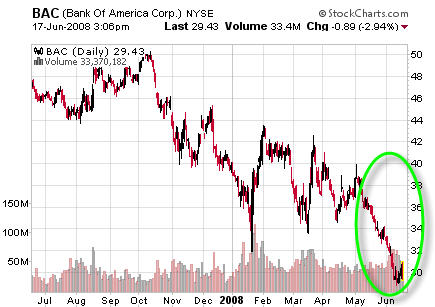

First up is Bank of America (BAC): $130 billion in market capitalization, a giant bank, and the highest bidder for Countrywide Financial Corp (CFC). BAC has lost 42% of its value over the past 8 months and is 10% lower than it was even at its lowest in March. This is an ugly chart and says that BAC is in some pretty serious trouble. Based on this one chart alone, we can say "no, it’s not over yet."

Now, maybe the market is frowning upon the fact that BAC seems intent, for some reason, on going ahead with their purchase of Countrywide (CFC), which, to this observer, ranks as one of the least fiscally-sound moves of all time. I mean, CFC is saddled with an enormous portfolio of non-performing subprime, no-doc, and option ARM mortgages, not to mention more than 15,000 repossessed properties.

Now, maybe the market is frowning upon the fact that BAC seems intent, for some reason, on going ahead with their purchase of Countrywide (CFC), which, to this observer, ranks as one of the least fiscally-sound moves of all time. I mean, CFC is saddled with an enormous portfolio of non-performing subprime, no-doc, and option ARM mortgages, not to mention more than 15,000 repossessed properties.

If this is true, then the market should be rewarding the CFC share price while punishing the BAC share price. Let’s see if that’s true…

Nope, it’s not true. That, my friends, is as ugly as it gets, and is the chart of a soon-to-be-bankrupt company. So we can pretty much conclude that BAC and CFC are being hammered on the basis of their business models and not as a result of their unholy alliance.

Nope, it’s not true. That, my friends, is as ugly as it gets, and is the chart of a soon-to-be-bankrupt company. So we can pretty much conclude that BAC and CFC are being hammered on the basis of their business models and not as a result of their unholy alliance.

So, what sort of issues could the stock price be telegraphing about BAC? Let’s consider that BAC has a grand total of ~$150 billion in equity, but over $700 billion in level 2 assets (i.e. "modeled value") and an astounding $32,000 billion in derivatives on the books.

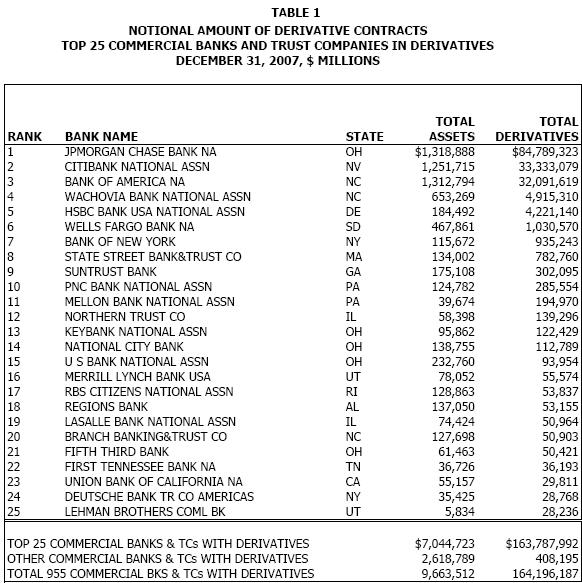

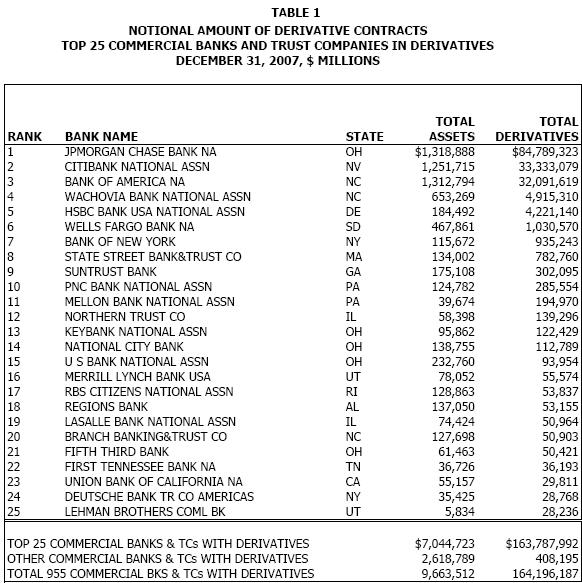

In fact, let me print the list of banks with significant derivative exposure, because I’ll be referring to several of these banks here:

There’s BAC, sitting at #3 on the list with an enormous derivative exposure, and their stock price is sinking like a stone. If Bernanke, et al., are not connecting these dots, then I am extremely worried, because it means they do not know trouble when they see it. But these are really smart folks, so we can fully assume that they are even more aware of this than anybody, leaving us to scratch our heads and wonder why their words do not even remotely match the situation. "Behind us?" Please, not a chance. This thing is just getting underway.

There’s BAC, sitting at #3 on the list with an enormous derivative exposure, and their stock price is sinking like a stone. If Bernanke, et al., are not connecting these dots, then I am extremely worried, because it means they do not know trouble when they see it. But these are really smart folks, so we can fully assume that they are even more aware of this than anybody, leaving us to scratch our heads and wonder why their words do not even remotely match the situation. "Behind us?" Please, not a chance. This thing is just getting underway.

Tip: If you bank with a company whose share price is sinking like a stone, you should think carefully about the joys and sorrows of becoming part of a massive FDIC receivership process.

Speaking of bank stocks giving off some bad odors, consider these:

Citigroup: $107B market cap, 62% loss within the past year, #2 on the derivative list.

Description: Citigroup Inc. (Citigroup)is a diversified global financial services holding company whose businesses provide a range of financial services to consumer and corporate customers. The Company is a bank holding company. As of March 31, 2008, Citigroup was organized into four major segments: Consumer Banking, Global Cards, Institutional Clients Group (ICG) and Global Wealth Management (GWM). The Company has more than 200 million customer accounts and does business in more than 100 countries.

Description: Citigroup Inc. (Citigroup)is a diversified global financial services holding company whose businesses provide a range of financial services to consumer and corporate customers. The Company is a bank holding company. As of March 31, 2008, Citigroup was organized into four major segments: Consumer Banking, Global Cards, Institutional Clients Group (ICG) and Global Wealth Management (GWM). The Company has more than 200 million customer accounts and does business in more than 100 countries.

Wachovia: $36B market cap, 65% loss over the past 8 months, #4 on the derivative list.

Description: Wachovia Corporation (Wachovia) is a financial holding company and a bank holding company. It provides commercial and retail banking, and trust services through full-service banking offices in 23 states.

Description: Wachovia Corporation (Wachovia) is a financial holding company and a bank holding company. It provides commercial and retail banking, and trust services through full-service banking offices in 23 states.

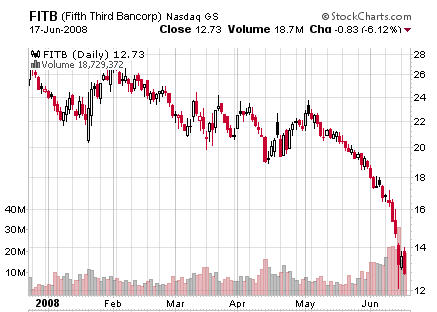

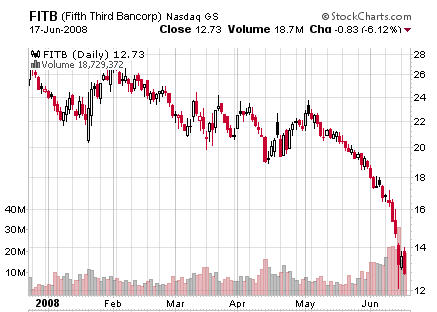

Fifth Third Bank Corp: $6.8B market cap, 70% loss within the past year, #21 on the derivative list.

Description: Fifth Third Bancorp (the Bancorp) is a diversified financial services company. As of December 31, 2007, the Bancorp operated 18 affiliates with 1,227 full-service banking centers, including 102 Bank Mart locations open seven days a week inside select grocery stores and 2,211 Jeanie automated teller machines (ATMs) in Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, Florida, Tennessee, West Virginia, Pennsylvania and Missouri

Description: Fifth Third Bancorp (the Bancorp) is a diversified financial services company. As of December 31, 2007, the Bancorp operated 18 affiliates with 1,227 full-service banking centers, including 102 Bank Mart locations open seven days a week inside select grocery stores and 2,211 Jeanie automated teller machines (ATMs) in Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, Florida, Tennessee, West Virginia, Pennsylvania and Missouri

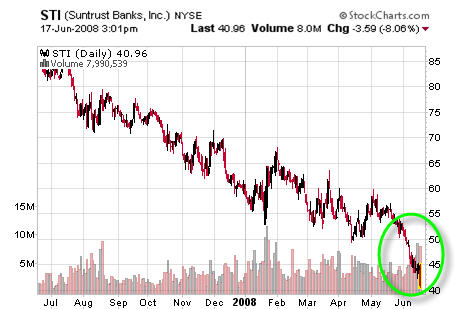

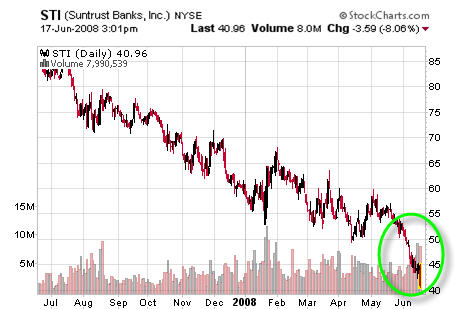

Suntrust Bank: $14b market cap, 55% loss within the past year, #9 on the derivative list.

Description: SunTrust Bank (the Bank), the Company provides deposit, credit, and trust and investment services. Through its subsidiaries, SunTrust also provides mortgage banking, credit-related insurance, asset management, securities brokerage and capital market services. The Company operates in five business segments: Retail, Commercial, Corporate and Investment Banking (CIB), Wealth and Investment Management, and Mortgage. The Bank operates primarily in Florida, Georgia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia and the District of Columbia.

Description: SunTrust Bank (the Bank), the Company provides deposit, credit, and trust and investment services. Through its subsidiaries, SunTrust also provides mortgage banking, credit-related insurance, asset management, securities brokerage and capital market services. The Company operates in five business segments: Retail, Commercial, Corporate and Investment Banking (CIB), Wealth and Investment Management, and Mortgage. The Bank operates primarily in Florida, Georgia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia and the District of Columbia.

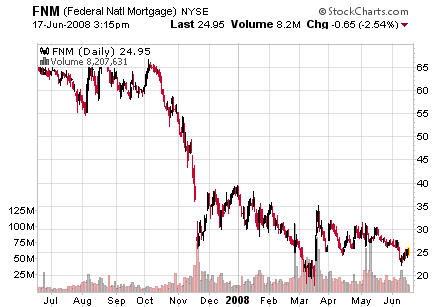

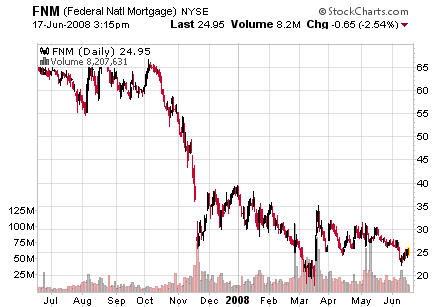

Fannie Mae: $24B market cap, 65% loss within the past year. Derivative exposure unknown.

Description: Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) is engaged in providing funds to mortgage lenders through its purchases of mortgage assets, and issuing and guaranteeing mortgage-related securities that facilitate the flow of additional funds into the mortgage market. The Company also makes other investments that increase the supply of affordable housing. It is a government-sponsored enterprise (GSE) chartered by the United States Congress and is aligned with national policies to support expanded access to housing and increased opportunities for homeownership. The Company is organized in three business segments: Single-Family Credit Guaranty, Housing and Community Development, and Capital Markets.

Description: Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) is engaged in providing funds to mortgage lenders through its purchases of mortgage assets, and issuing and guaranteeing mortgage-related securities that facilitate the flow of additional funds into the mortgage market. The Company also makes other investments that increase the supply of affordable housing. It is a government-sponsored enterprise (GSE) chartered by the United States Congress and is aligned with national policies to support expanded access to housing and increased opportunities for homeownership. The Company is organized in three business segments: Single-Family Credit Guaranty, Housing and Community Development, and Capital Markets.

General Electric: $287B market cap, 31% loss within the past year, derivative exposure unknown. Note: GE is hugely exposed to finance through its GE Capital division – some wags say that GE is a finance company that also makes stuff.

Description: General Electric Company (GE) is a diversified technology, media and financial services company. With products and services ranging from aircraft engines, power generation, water processing and security technology to medical imaging, business and consumer financing, media content and industrial products, it serves customers in more than 100 countries. GE operates in six segments: Infrastructure, Commercial Finance, GE Money, Healthcare, NBC Universal and Industrial.

Description: General Electric Company (GE) is a diversified technology, media and financial services company. With products and services ranging from aircraft engines, power generation, water processing and security technology to medical imaging, business and consumer financing, media content and industrial products, it serves customers in more than 100 countries. GE operates in six segments: Infrastructure, Commercial Finance, GE Money, Healthcare, NBC Universal and Industrial.

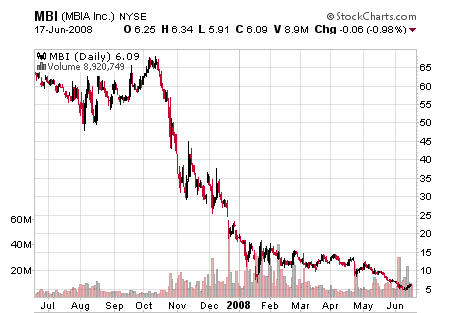

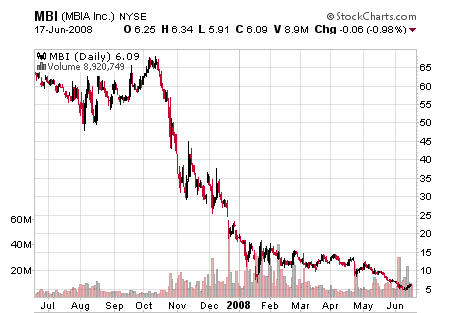

MBIA: $1.6B market cap, 91% loss within the past year, exposed to $137 billion in Credit Default Swaps.

Description: MBIA Inc. (MBIA) is engaged in providing financial guarantee insurance and other forms of credit protection, as well as investment management services to public finance and structured finance issuers, investors and capital market participants on a global basis.

Description: MBIA Inc. (MBIA) is engaged in providing financial guarantee insurance and other forms of credit protection, as well as investment management services to public finance and structured finance issuers, investors and capital market participants on a global basis.

Each one of the above examples is signaling a severe financial crisis. These examples, of which I could pull many more, represent the largest financial company in the world (Fannie Mae), one of the largest banks in the world (BAC), two regional banks (Suntrust and Fifth Third), a national bank (Wachovia), the third largest company in the world (GE), a bond insurance company (MBIA), and a pure-play mortgage company (CFC). In short, we are seeing severe financial weakness across a diverse set of sectors, regions, and products, and I am at a complete loss as to how anyone could view these charts and make the claim that we are out of the woods.

Tip: If your bank is publicly traded, follow the stock closely. At any sign of weakness, get out and get safe.

Summary

Okay, why did I drag you through this tour of stock charts? Because I desperately want you to understand that this party is just getting started. The comforting words of the Federal Reserve are grossly mismatched to the price signals that these very large and very leveraged financial companies are giving off. The charts above are screaming that "something is broken." I don’t know exactly what it is, but my suspicion is that the derivative mess is at the heart of it.

My analysis suggests that the FDIC lacks sufficient funds to adequately insure all of the potential losses. Read my report on the FDIC if you need a refresher on the matter.

As go the financial companies, so goes America.

That’s what this fight is all about, and that is why the Fed is pouring liquidity on the markets even as inflation is screaming higher and ruining lives. The alternative, collapse of our banking system, is viewed as the far greater threat.

And rightly so.

Actions you can take

Financial Distress – Bank Stocks Reveal Urgent Weakness

PREVIEW by Chris MartensonWednesday, June 18, 2008

Executive Summary

- Relatively benign stock market index performance is masking severe financial weakness

- Judging by their stock charts, several good-sized banks might file for bankruptcy soon

- Financial market liquidity supplied by the Fed is at odds with their words that "credit market conditions are improving"

- The assets of the banks under duress are many, many multiples of total FDIC assets

"Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain!" barks the booming voice.

Unfortunately for the dumpy, balding ‘wizard,’ the curtain has already been removed and he’s been spotted.

The first two weeks of June (2008) have been all about knowing where to look. Let’s peel back the curtain.

Let me begin with a personal story. One of my main trading accounts was with a company called Lind-Waldock, a very reputable, stable, old company that got bought out by fast-flying Refco. All seemed well for the first few months, I had the same broker at the other end of the phone and I noticed no difference in my trading experience. But I was wary of Refco, so I kept a live stock chart up on my computer monitor, which I kept a close eye on. One day, the stock price of Refco took a stomach-wrenching dive, losing nearly 20% in a single hour. I immediately called my broker and shifted my funds out of that company that very day. I even got a call from the head of the division asking me to remain, insisting that all was well, and explaining that the stock was falling on the basis of unsubstantiated and certainly untrue rumors. It turns out that the rumors were true; Refco was involved in some shenanigans and had clumsily tried to hide billions in losses by stuffing them in an off-shore subsidiary. Refco was actually insolvent and ultimately went bankrupt. And it was also true that my money would have been safe even had I not moved it, but my position on these matters is to bring the money home and ask the detailed questions later.

Below you will see many examples of stock price performance that would cause me personally to remove my money to a safer location and save the questions for later.

After the dangerous downdraft in the dollar and the stock market seen on Friday the 6th of June, the Federal Reserve and their brethren in Europe, the ECB, were all over the airwaves beginning Sunday the 8th in an attempt to prevent the markets from selling off any further. Judging by the headline stock index performance, they did pretty well, as the indexes closed more or less unchanged for the week. However, if we peek behind the curtains, we see something very different.

I want to focus on the issue of banks and bank solvency. Actually, I want to broaden this definition to include what are termed "financial institutions," which include mortgage brokers and commercial lending institutions. Why? Because we are now a financial economy. Measured in dollars, our economy has much more activity in the business of moving money around than it does in the manufacturing real goods.

It used to be said that "as goes GM, so goes the US," meaning that the economic health of the country could be measured by the activity of its (formerly) largest manufacturer. Now it might be said that "as goes JP Morgan, so goes the country."

Here are the warning signs that major and probably systemic financial distress remains threaded throughout our economy like termite tunnels in a load-bearing beam.

The Fed’s words and actions are not aligned

Bernanke recently said that the risk the economy has entered a substantial downturn "appears to have diminished over the past month or so," while Alan Greenspan said that financial markets have shown a "pronounced turnaround" since March. Which leads us to the recent inflation-fighting words of Bernanke, who said that the Fed would "strongly resist" expectations that inflation will accelerate, hinting at the possibility that interest rates will be raised. Of course, all of these are simply words. What are the actions?

Since you and I know that inflation is caused by too much money lent too cheaply, we’ll spend less time listening to words and more time looking at the monetary data. In other words, let’s pay attention to what they are doing, not what they are saying.

Through a combination of Federal Reserve and Treasury actions, the total amount of liquidity that has been injected into the banking system has advanced over $40 billion in the last 10 days, smashing to a new all-time record of more than $307 billion dollars. If the worst was behind us and inflation was a real concern, this would not have happened. The actions here tell us that the fear of whatever is ailing the banking system vastly outweighs any concerns about inflation.

Further, short-term interest rates are set at 2.0%, which is a full two percent below the rate of inflation. What do you get when you combine negative real interest rates with extremely loose monetary policy? Inflation.

And finally, here’s a chart of the money supply of this nation. If this was a roller coaster ride, you’d be pressed back in your seat staring at the sky – not unlike oil, grains, and other basic commodities.

So there you have it: On the one side, record amounts of liquidity, deeply negative real interest rates, and a near-vertical rise in monetary aggregates. And on the other side, words.

So there you have it: On the one side, record amounts of liquidity, deeply negative real interest rates, and a near-vertical rise in monetary aggregates. And on the other side, words.

Bank and financial stocks under attack

When I want to know how a company is doing, I turn to a chart of its stock price. Long before the headlines are written of a company’s undoing, the stock price has already told the tale. The story currently being told by the stock price of several mid-sized banks, mortgage companies, and bond insurers is nothing short of a disaster in the making.

You need to be paying attention to these next few charts. Remember, Bernanke and Greenspan want you to think that the worst is behind us and that things turned around in March.

First up is Bank of America (BAC): $130 billion in market capitalization, a giant bank, and the highest bidder for Countrywide Financial Corp (CFC). BAC has lost 42% of its value over the past 8 months and is 10% lower than it was even at its lowest in March. This is an ugly chart and says that BAC is in some pretty serious trouble. Based on this one chart alone, we can say "no, it’s not over yet."

Now, maybe the market is frowning upon the fact that BAC seems intent, for some reason, on going ahead with their purchase of Countrywide (CFC), which, to this observer, ranks as one of the least fiscally-sound moves of all time. I mean, CFC is saddled with an enormous portfolio of non-performing subprime, no-doc, and option ARM mortgages, not to mention more than 15,000 repossessed properties.

Now, maybe the market is frowning upon the fact that BAC seems intent, for some reason, on going ahead with their purchase of Countrywide (CFC), which, to this observer, ranks as one of the least fiscally-sound moves of all time. I mean, CFC is saddled with an enormous portfolio of non-performing subprime, no-doc, and option ARM mortgages, not to mention more than 15,000 repossessed properties.

If this is true, then the market should be rewarding the CFC share price while punishing the BAC share price. Let’s see if that’s true…

Nope, it’s not true. That, my friends, is as ugly as it gets, and is the chart of a soon-to-be-bankrupt company. So we can pretty much conclude that BAC and CFC are being hammered on the basis of their business models and not as a result of their unholy alliance.

Nope, it’s not true. That, my friends, is as ugly as it gets, and is the chart of a soon-to-be-bankrupt company. So we can pretty much conclude that BAC and CFC are being hammered on the basis of their business models and not as a result of their unholy alliance.

So, what sort of issues could the stock price be telegraphing about BAC? Let’s consider that BAC has a grand total of ~$150 billion in equity, but over $700 billion in level 2 assets (i.e. "modeled value") and an astounding $32,000 billion in derivatives on the books.

In fact, let me print the list of banks with significant derivative exposure, because I’ll be referring to several of these banks here:

There’s BAC, sitting at #3 on the list with an enormous derivative exposure, and their stock price is sinking like a stone. If Bernanke, et al., are not connecting these dots, then I am extremely worried, because it means they do not know trouble when they see it. But these are really smart folks, so we can fully assume that they are even more aware of this than anybody, leaving us to scratch our heads and wonder why their words do not even remotely match the situation. "Behind us?" Please, not a chance. This thing is just getting underway.

There’s BAC, sitting at #3 on the list with an enormous derivative exposure, and their stock price is sinking like a stone. If Bernanke, et al., are not connecting these dots, then I am extremely worried, because it means they do not know trouble when they see it. But these are really smart folks, so we can fully assume that they are even more aware of this than anybody, leaving us to scratch our heads and wonder why their words do not even remotely match the situation. "Behind us?" Please, not a chance. This thing is just getting underway.

Tip: If you bank with a company whose share price is sinking like a stone, you should think carefully about the joys and sorrows of becoming part of a massive FDIC receivership process.

Speaking of bank stocks giving off some bad odors, consider these:

Citigroup: $107B market cap, 62% loss within the past year, #2 on the derivative list.

Description: Citigroup Inc. (Citigroup)is a diversified global financial services holding company whose businesses provide a range of financial services to consumer and corporate customers. The Company is a bank holding company. As of March 31, 2008, Citigroup was organized into four major segments: Consumer Banking, Global Cards, Institutional Clients Group (ICG) and Global Wealth Management (GWM). The Company has more than 200 million customer accounts and does business in more than 100 countries.

Description: Citigroup Inc. (Citigroup)is a diversified global financial services holding company whose businesses provide a range of financial services to consumer and corporate customers. The Company is a bank holding company. As of March 31, 2008, Citigroup was organized into four major segments: Consumer Banking, Global Cards, Institutional Clients Group (ICG) and Global Wealth Management (GWM). The Company has more than 200 million customer accounts and does business in more than 100 countries.

Wachovia: $36B market cap, 65% loss over the past 8 months, #4 on the derivative list.

Description: Wachovia Corporation (Wachovia) is a financial holding company and a bank holding company. It provides commercial and retail banking, and trust services through full-service banking offices in 23 states.

Description: Wachovia Corporation (Wachovia) is a financial holding company and a bank holding company. It provides commercial and retail banking, and trust services through full-service banking offices in 23 states.

Fifth Third Bank Corp: $6.8B market cap, 70% loss within the past year, #21 on the derivative list.

Description: Fifth Third Bancorp (the Bancorp) is a diversified financial services company. As of December 31, 2007, the Bancorp operated 18 affiliates with 1,227 full-service banking centers, including 102 Bank Mart locations open seven days a week inside select grocery stores and 2,211 Jeanie automated teller machines (ATMs) in Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, Florida, Tennessee, West Virginia, Pennsylvania and Missouri

Description: Fifth Third Bancorp (the Bancorp) is a diversified financial services company. As of December 31, 2007, the Bancorp operated 18 affiliates with 1,227 full-service banking centers, including 102 Bank Mart locations open seven days a week inside select grocery stores and 2,211 Jeanie automated teller machines (ATMs) in Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana, Michigan, Illinois, Florida, Tennessee, West Virginia, Pennsylvania and Missouri

Suntrust Bank: $14b market cap, 55% loss within the past year, #9 on the derivative list.

Description: SunTrust Bank (the Bank), the Company provides deposit, credit, and trust and investment services. Through its subsidiaries, SunTrust also provides mortgage banking, credit-related insurance, asset management, securities brokerage and capital market services. The Company operates in five business segments: Retail, Commercial, Corporate and Investment Banking (CIB), Wealth and Investment Management, and Mortgage. The Bank operates primarily in Florida, Georgia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia and the District of Columbia.

Description: SunTrust Bank (the Bank), the Company provides deposit, credit, and trust and investment services. Through its subsidiaries, SunTrust also provides mortgage banking, credit-related insurance, asset management, securities brokerage and capital market services. The Company operates in five business segments: Retail, Commercial, Corporate and Investment Banking (CIB), Wealth and Investment Management, and Mortgage. The Bank operates primarily in Florida, Georgia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia and the District of Columbia.

Fannie Mae: $24B market cap, 65% loss within the past year. Derivative exposure unknown.

Description: Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) is engaged in providing funds to mortgage lenders through its purchases of mortgage assets, and issuing and guaranteeing mortgage-related securities that facilitate the flow of additional funds into the mortgage market. The Company also makes other investments that increase the supply of affordable housing. It is a government-sponsored enterprise (GSE) chartered by the United States Congress and is aligned with national policies to support expanded access to housing and increased opportunities for homeownership. The Company is organized in three business segments: Single-Family Credit Guaranty, Housing and Community Development, and Capital Markets.

Description: Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) is engaged in providing funds to mortgage lenders through its purchases of mortgage assets, and issuing and guaranteeing mortgage-related securities that facilitate the flow of additional funds into the mortgage market. The Company also makes other investments that increase the supply of affordable housing. It is a government-sponsored enterprise (GSE) chartered by the United States Congress and is aligned with national policies to support expanded access to housing and increased opportunities for homeownership. The Company is organized in three business segments: Single-Family Credit Guaranty, Housing and Community Development, and Capital Markets.

General Electric: $287B market cap, 31% loss within the past year, derivative exposure unknown. Note: GE is hugely exposed to finance through its GE Capital division – some wags say that GE is a finance company that also makes stuff.

Description: General Electric Company (GE) is a diversified technology, media and financial services company. With products and services ranging from aircraft engines, power generation, water processing and security technology to medical imaging, business and consumer financing, media content and industrial products, it serves customers in more than 100 countries. GE operates in six segments: Infrastructure, Commercial Finance, GE Money, Healthcare, NBC Universal and Industrial.

Description: General Electric Company (GE) is a diversified technology, media and financial services company. With products and services ranging from aircraft engines, power generation, water processing and security technology to medical imaging, business and consumer financing, media content and industrial products, it serves customers in more than 100 countries. GE operates in six segments: Infrastructure, Commercial Finance, GE Money, Healthcare, NBC Universal and Industrial.

MBIA: $1.6B market cap, 91% loss within the past year, exposed to $137 billion in Credit Default Swaps.

Description: MBIA Inc. (MBIA) is engaged in providing financial guarantee insurance and other forms of credit protection, as well as investment management services to public finance and structured finance issuers, investors and capital market participants on a global basis.

Description: MBIA Inc. (MBIA) is engaged in providing financial guarantee insurance and other forms of credit protection, as well as investment management services to public finance and structured finance issuers, investors and capital market participants on a global basis.

Each one of the above examples is signaling a severe financial crisis. These examples, of which I could pull many more, represent the largest financial company in the world (Fannie Mae), one of the largest banks in the world (BAC), two regional banks (Suntrust and Fifth Third), a national bank (Wachovia), the third largest company in the world (GE), a bond insurance company (MBIA), and a pure-play mortgage company (CFC). In short, we are seeing severe financial weakness across a diverse set of sectors, regions, and products, and I am at a complete loss as to how anyone could view these charts and make the claim that we are out of the woods.

Tip: If your bank is publicly traded, follow the stock closely. At any sign of weakness, get out and get safe.

Summary

Okay, why did I drag you through this tour of stock charts? Because I desperately want you to understand that this party is just getting started. The comforting words of the Federal Reserve are grossly mismatched to the price signals that these very large and very leveraged financial companies are giving off. The charts above are screaming that "something is broken." I don’t know exactly what it is, but my suspicion is that the derivative mess is at the heart of it.

My analysis suggests that the FDIC lacks sufficient funds to adequately insure all of the potential losses. Read my report on the FDIC if you need a refresher on the matter.

As go the financial companies, so goes America.

That’s what this fight is all about, and that is why the Fed is pouring liquidity on the markets even as inflation is screaming higher and ruining lives. The alternative, collapse of our banking system, is viewed as the far greater threat.

And rightly so.

Actions you can take

Tuesday, May 27, 2008

Executive Summary

- In this report, I lay out my near- and intermediate-term investment themes.

- My assessment is that the economic and financial risks are exceptionally high and possibly historically unique. This is no time for complacency. A defensive stance is both warranted and prudent. A 50% – 70% (real) decline in the main stock market indexes is a distinct possibility, and portfolios should be ‘crash-proofed.’

- Heeding the calls that “a bottom is in” and “the recession could already be over” could be hazardous to your wealth.

- The recession is just beginning and will be the worst in several generations.

- Residential housing data is still accelerating to the downside, while commercial real estate is just beginning its long date with tough times. There is no bottom in sight for either.

- Inflation for life’s necessities is up, and rising energy costs will likely keep certain items at persistently high – and rising – prices for a very long time.

Bottom line: My assessment is that the financial and economic risks that currently exist are exceptional, historically unique, and possibly systemic in nature, and therefore call for non-status-quo responses. A defensive stance is both warranted and prudent. As for timing, my motto is, ‘I’d rather be a year early than a day late.’

Some Context

I am an educator and a communicator, and I focus on using the past to view the future. Some might consider me a futurist. I think of myself as a realist, and I try to let the data inform me about what’s going on. Of course, the extent to which the data is flawed represents the risk of being wrong.

My goal is not to simply inform, but to inform in a way that leads to you take actions. I want you to protect what you’ve got and prepare for a future that will, in all likelihood, be very different from the present. So different, in fact, that I think you should begin making changes to your lifestyle as soon as possible. In my own life I have found that the mental, physical, and financial actions I am advocating take a considerable amount of time to implement.

Broadly speaking, they are:

- Adapting to a general decline in Western standards of living. The servicing of past debts, coupled with relentless fuel price increases and a recession, speak to a massive shift in our buying and consuming habits. We’ll all have to find ways to be happy with less stuff. This is actually a good thing.

- Moving from a culture of “I” to “we.” The strength and depth of your community connections are going to increase in importance as time goes on. Needless to say, these connections cannot be manufactured overnight. They take energy and thoughtfulness, while trust requires time.

- Giving up the belief (or the certainty?) that the future will be like today, only bigger, and filled with more opportunities for the next generation(s). Maybe it will, and maybe it won’t. I personally found this belief the hardest to let go of because it comes with a sense of loss. I finally progressed past this blockage when I began to believe that the future will simply consist of new and different opportunities than today. But that took work. And time.

- Relying more greatly upon ‘self.’ I use this term broadly to include my entire region. While it may be true that oil and food will continue to flow to New England in sufficient and desired (required?) quantities, what if they don’t?

A Disclaimer and Some Good News

One thing that I cannot and will not do is give specific investment advice to individuals. For legal reasons, I cannot name companies or individual mutual funds, or anything else specific, except in the context of my role as an educator on these matters.

Which is fine by me, because I don’t want to be in the business of analyzing and recommending specific companies, bond offerings, or mutual funds.

To do this credibly and responsibly, I’d have to begin the immense process of sifting through all 20,000+ individual stocks and funds…and I simply don’t have the resources or time. Luckily, there are a lot of qualified people who do this professionally.

Rather, my work involves laying out themes against which specific investment opportunities and strategies can be assessed. I will lay out these themes, and even tell you what I’ve done in response, but it’s up to you to mesh them with your particular situation.

And now for the good news. For anybody who is interested, I (finally!) have a short list of investment advisors who have seen the Crash Course, largely agree with its premises, and are willing to work with people to manage their holdings accordingly. Imagine what it would be like to talk with an advisor who sees the same financial risks that you do, takes them seriously, and has already formulated a response to each of them.

I have no financial relationship with any of these advisors, will never take anything in return from them, and will not recommend one over another. You may request that I provide you with their names and phone numbers (never the other way around), but it will be up to you to make contact and assess the fit. However, I am thrilled to finally have a pool of financial advisors to whom I can refer people. What I get out of this is the satisfaction of knowing that I could help fulfill a very important need. Simply email me and I will forward their contact information to you.

My Themes

So, what does the future hold? Here I will admit that I cannot find any clear historical precedents against which to contrast our current state of affairs. The combination of a national lack of savings, record levels of debt, a failure to invest (in capital and infrastructure), an aging population, Peak Oil, and insolvent entitlement and pension programs has never before been encountered by humans. Worse, Alan Greenspan suckered, er, influenced the rest of the world to go along with the largest credit bubble in all of history, and so there are fewer ways to diversify internationally than might otherwise have been true.

Because the past can only provide clues, I’ve been analyzing and investing according to ‘themes’ that rely on equal parts of data, logic, and my faith that people will tend to behave as they have in the past. And let me repeat that you can count on me to change my view when the data supports a shift. Within the context of these themes, there will always be individual winners and losers. Threats and opportunities always exist side by side. Our task is to choose wisely. My major themes for the next few years are:

Theme #1: Recession, or possibly a depression, due to the bursting of the largest credit bubble in history

My concern level is “high” and stretches from right now until late 2009 to 2010. Nobody alive has ever lived through the bursting of a global credit bubble, and history offers only clues and hints as to how this all might unfold. Your guesses are as good (or as bad) as mine. The recession/depression is going to be fueled by:

- The return of household savings. If households returned to saving even just 5% compared to the current 0%, then the impact to the economy would be the loss of 3.5% of GDP. If this happened, all by itself it would contribute to one of the worst economic periods in modern times.

- Job losses. As the credit bubble bursts, credit will become harder and harder to obtain, businesses will fold, and job losses will mount. Some regions, like Detroit (cars) and Orlando (tourism) will be especially hard hit. Certain job sectors will be particularly vulnerable, especially those related to discretionary or lavish spending.

STRATEGY: Remain alert. Cut spending, reduce debt, and build savings. Be prepared to revisit portfolio assumptions and tactics on a more frequent (Quarterly? Monthly? Weekly?) basis.

WINNERS: If a deflationary recession/depression, cash and high-grade bonds. If an inflationary recession/depression, energy, commodities, and consumer staples. In either case, only a very select group of stocks will perform well. The rest will suffer big losses.

LOSERS: Stock index funds, low yielding stocks, and non-investment grade bonds. Everybody who failed to take this prospect seriously and plan properly.

Theme #2: Inflation is here and rising

(This is a near-term concern). I will remain concerned about inflation until I see my fiscal and monetary authorities begin to behave rationally. At present, the only concern I see on their parts is to ‘reflate’ the banking system at any and all costs. One of those costs is inflation. My full list of inflation concerns is as follows:

- Dollar weakness. Even if the rest of the world experiences no inflation, if our dollar falls, we will still see rising prices for oil and all of the other essential products we import.

- Supply and demand mismatch (for oil and grains especially). If there is a long-term imbalance created by the fact that the earth can no longer provide a surplus of the things that humans want/need, then prices for the desired items will consume an ever-greater share of our respective budgets.

- Structural inflation (e.g., higher oil prices make steel more expensive, leading to higher drilling costs, leading to higher oil prices….etc). Once a structural inflation spiral gets started, it is a very difficult thing to stop. Such is currently the case for food and fuel.

- Monetary inflation (growth in MZM & M3 are at historical highs). And it’s not just the US. Inflation is spiking all over the world in lockstep with exploding money supply figures. One of the hallmarks of the Great Depression was a nasty series of competitive devaluations by various countries, as they attempted to preserve their manufacturing jobs by making their products appear cheaper than others. This is a very ordinary and predictable response, as it represents both the appearance of ‘doing something’ and the path of least resistance. That makes it practically irresistible to even an above-average politician.

- Likely actions by fiscal and monetary authorities. Spending and easing, respectively, are heavily weighted towards inflation.

STRATEGY: Buy your essential items early and often. Stock up your pantry and find ways to store more items in and around your house. Don’t hold cash or cash equivalents, and avoid long-dated bonds, especially those offering negative real returns (i.e., a yield below the rate of inflation). Be prepared to move out of paper assets altogether and into tangible wealth. Productive land might be one avenue to explore.

WINNERS: Commodities, and stocks with a positive inflation sensitivity and/or strong pricing power (like energy and consumer staples companies).

LOSERS: Bonds paying a negative real rate; companies with low pricing power. Remember, it’s your real return that matters, not your nominal return. The Zimbabwe stock market is up tens of thousands of percent this year. Unfortunately, their inflation is up hundreds of thousands of percent. Stocks that don’t keep pace with inflation are another way to lose.

Theme #3: Potential banking system insolvency

(This is also a near-term concern). Yes, the Fed was able to patch things up for a while. No, the danger has not passed. Financial stocks are still getting killed in the market, and I am keeping an especially close eye on Lehman Brothers (LEH), as their stock took a particular beating at the end of last week (May 21 – 23, 2008). It won’t take too many more major financial companies going bust due to derivative-based wipeouts before the whole system goes into shock. Beyond that, here’s the basic data that gives me the most concern:

- Financial companies are holding $5 trillion (with a “t”) in level 3 assets, which utterly dwarfs the Federal Reserve balance sheet (what remains of it) and possibly even dwarfs the borrowing ability of the US government. Level 3 assets are an accounting gimmick that allow executives to place whatever value they deem appropriate on ‘hard to value’ items, like bundles of subprime mortgages that really aren’t worth all that much. Needless to say, there’s some incentive to, shall we say, be generous with the estimates of value.

- Certain derivative products, specifically credit default swaps and collateralized debt obligations, total in the tens of trillions of dollars, and their markets are in disarray. Counterparty risk is unknown and possibly unknowable. The risk here is unacceptable. If these markets spin out of control into a series of cascading cross-defaults, my main question will be, “What will happen to our financial system?” which leads to, “What will happen to financial investments?”

- Total bank capital stands at $1.1 trillion, but the potential total losses across all residential and commercial real estate are much higher than that. While a massive public bailout is probably in the cards, that will take time, and even I am shocked at how fast the housing market is deteriorating across several extremely large markets (notably all of CA, FL, Las Vegas, Phoenix, and Denver). Again, the pace of the collapse is what defines the risk here, while the magnitude is without historical precedent.

STRATEGY: Don’t have all your eggs in one basket – use several highly-rated banks. Remain liquid and alert; be prepared to access and move your funds away from troubled institutions as a tactic to avoid becoming enmeshed in a receivership process.

WINNERS: People with their dollars held by strong banks, and those who don’t have all their wealth tied up in the banking system and are holding cash, gold, silver, and other sources of liquid, non-dollar-denominated wealth completely outside of the financial system. Having strong, dependable community networks to help manage the transition period.

LOSERS: Everybody who is late to recognize that bank failures have begun and/or has their money tied up in an insolvent bank. If a generalized bank system failure does occur, we all lose, to some degree.

Theme #4: Peak Oil

This theme offers both tremendous risk and enormous opportunity. This used to be a medium-term concern of mine (2-10 years out), but has recently become a near-term concern. I happen to believe it is here right now, and the only thing that could mask it for a bit longer would be a global depression. A recession probably wouldn’t do it, though, because through all of history the largest ever yr/yr drop in global oil demand was a mere 0.4%, and that was after a particularly nasty recession back in the 1970’s…meaning it will take more than a garden-variety recession to produce the required 2%-3% drop in demand to mask declining oil production.

STRATEGY: Begin to whittle down your dependence on energy as a means of reducing the energy portion of your daily budget.

WINNERS: Energy investments of all sorts, ranging from traditional to alternative and from producers to servicers. Those with the lowest proportion of spending on energy and access to alternative modes of heating, cooling, and transportation. My prediction here is that once Peak Oil is generally recognized, solar systems will suddenly develop multi-year waiting periods.

LOSERS: An enormously wide range of companies that are built around cheap energy. Certain SUV-dependent auto manufacturers come to mind.

Theme #5: Boomer retirement

The retirement of the baby boomers will result in drawdowns that will exceed Gen-X buy-ups. To whom are the boomers going to sell all of their assets? Or, what happens when Cal-Pers (et al.) becomes a net seller rather than a net buyer? (This is a long-term concern…as in, 10 years out). Unfortunately, this retirement boom will create demands upon financial investments, concurrent with vast national needs to re-tool our energy, sewage, water, electrical, and transportation systems. Here I am expecting a toxic combination of both falling asset prices (in real terms) and rising tax bills, as our politicians attempt to simultaneously fix everything they’ve been ignoring for the past two decades.

STRATEGY: Begin reducing total exposure to everything in which boomers are overinvested. This includes stocks, bonds, and McMansions. Avoid living in places or houses that require too much reliance on energy or have especially weak or overextended governments. Vallejo, CA (now bankrupt) is an example…tax bills there are remaining constant, even as services crumble and disappear.

WINNERS: Sectors that service retiring boomers.

LOSERS: High p/e ‘growth’ stocks, low dividend stocks, and other investments whose gains largely depend on persistent and sustained buying pressure. Second homes located in less than prime areas, especially those far from urban areas and therefore requiring large amounts of gasoline to access.

The Path

While it is possible, I do not anticipate a one-way slide to the bottom, wherever and whenever that may be. I lean towards the ‘stair-step’ model, where a series of sequential shocks and relatively placid periods mark the path to the future. The three possible scenarios around which I form my thinking (and actions) are:

- No change. The future looks just like today, only bigger, and no major upheavals, shocks, or recessions happen. The Fed and Congress are successful in fighting off the deleterious effects of the bursting of the housing bubble, and everybody carries on without any major changes or adjustments. This is not a very likely outcome. Probability: 1%.

- A series of short, sharp shocks. Moments of relative calm and seeming recovery are punctuated by rapid and unsettling market plunges and marked changes in social perspective. Think of the food scarcity and riots, and you know what this looks like. One day there is low awareness about food scarcity, and the next day shortages and prices spikes are making the news. Soon enough, relative calm returns, prices fall, and order is restored, but prices somehow do not recover to their previous levels, leaving people primed and alert for the next leg of the process. I see this as the most likely path forward. Probability: 80%.

- A sudden major collapse. Under this scenario, some sort of a tipping point causes a light-speed reaction in the global economic system that requires shutting down cross-border capital flows. Banks would no longer be able to clear transfers and accounts, which would wreak all sorts of havoc upon our just-in-time society. Food and fuel distribution would be the most immediate concerns. There’s enough of a chance of this scenario occurring, and the impacts are potentially so severe, that you should take actions to minimize the impacts to yourself and loved ones. Probability: ~20%.

Which of these three scenarios will actually unfold is, of course, unknown. This is why I maintain an alert stance, and why I am constantly sifting the news and posting my thoughts in my blog. Should a serious event warrant, I will send enrolled members an alert outlining the data and actions you should consider. I have not yet sent out a single alert because no single event has crossed my threshold. If (or when) you receive one from me, it will be about something I take very seriously.

Of course, nobody can make all the changes that are required at once, or even over the next year. Rather, there is a list of things that each of us, depending on our circumstances, should consider doing over the next few years. I break them down into three tiers of actions. Tier I actions are ones that you should do immediately. Tier II are ones that you would do only after finishing the Tier I actions. Tier III are longer-term actions that come after the first two are done, or can be worked in parallel, if time, money, and energy permit.

Let me close with this: My sincerest hope is that you begin the process of adapting your lifestyle, right now, to the new future that awaits. If you are waiting for the signs to become any clearer than this, you are waiting too long.

What are you waiting for?

Charting a Course Through the Recession

PREVIEW by Chris MartensonTuesday, May 27, 2008

Executive Summary

- In this report, I lay out my near- and intermediate-term investment themes.

- My assessment is that the economic and financial risks are exceptionally high and possibly historically unique. This is no time for complacency. A defensive stance is both warranted and prudent. A 50% – 70% (real) decline in the main stock market indexes is a distinct possibility, and portfolios should be ‘crash-proofed.’

- Heeding the calls that “a bottom is in” and “the recession could already be over” could be hazardous to your wealth.

- The recession is just beginning and will be the worst in several generations.

- Residential housing data is still accelerating to the downside, while commercial real estate is just beginning its long date with tough times. There is no bottom in sight for either.

- Inflation for life’s necessities is up, and rising energy costs will likely keep certain items at persistently high – and rising – prices for a very long time.

Bottom line: My assessment is that the financial and economic risks that currently exist are exceptional, historically unique, and possibly systemic in nature, and therefore call for non-status-quo responses. A defensive stance is both warranted and prudent. As for timing, my motto is, ‘I’d rather be a year early than a day late.’

Some Context

I am an educator and a communicator, and I focus on using the past to view the future. Some might consider me a futurist. I think of myself as a realist, and I try to let the data inform me about what’s going on. Of course, the extent to which the data is flawed represents the risk of being wrong.

My goal is not to simply inform, but to inform in a way that leads to you take actions. I want you to protect what you’ve got and prepare for a future that will, in all likelihood, be very different from the present. So different, in fact, that I think you should begin making changes to your lifestyle as soon as possible. In my own life I have found that the mental, physical, and financial actions I am advocating take a considerable amount of time to implement.

Broadly speaking, they are:

- Adapting to a general decline in Western standards of living. The servicing of past debts, coupled with relentless fuel price increases and a recession, speak to a massive shift in our buying and consuming habits. We’ll all have to find ways to be happy with less stuff. This is actually a good thing.

- Moving from a culture of “I” to “we.” The strength and depth of your community connections are going to increase in importance as time goes on. Needless to say, these connections cannot be manufactured overnight. They take energy and thoughtfulness, while trust requires time.

- Giving up the belief (or the certainty?) that the future will be like today, only bigger, and filled with more opportunities for the next generation(s). Maybe it will, and maybe it won’t. I personally found this belief the hardest to let go of because it comes with a sense of loss. I finally progressed past this blockage when I began to believe that the future will simply consist of new and different opportunities than today. But that took work. And time.

- Relying more greatly upon ‘self.’ I use this term broadly to include my entire region. While it may be true that oil and food will continue to flow to New England in sufficient and desired (required?) quantities, what if they don’t?

A Disclaimer and Some Good News

One thing that I cannot and will not do is give specific investment advice to individuals. For legal reasons, I cannot name companies or individual mutual funds, or anything else specific, except in the context of my role as an educator on these matters.

Which is fine by me, because I don’t want to be in the business of analyzing and recommending specific companies, bond offerings, or mutual funds.

To do this credibly and responsibly, I’d have to begin the immense process of sifting through all 20,000+ individual stocks and funds…and I simply don’t have the resources or time. Luckily, there are a lot of qualified people who do this professionally.

Rather, my work involves laying out themes against which specific investment opportunities and strategies can be assessed. I will lay out these themes, and even tell you what I’ve done in response, but it’s up to you to mesh them with your particular situation.

And now for the good news. For anybody who is interested, I (finally!) have a short list of investment advisors who have seen the Crash Course, largely agree with its premises, and are willing to work with people to manage their holdings accordingly. Imagine what it would be like to talk with an advisor who sees the same financial risks that you do, takes them seriously, and has already formulated a response to each of them.

I have no financial relationship with any of these advisors, will never take anything in return from them, and will not recommend one over another. You may request that I provide you with their names and phone numbers (never the other way around), but it will be up to you to make contact and assess the fit. However, I am thrilled to finally have a pool of financial advisors to whom I can refer people. What I get out of this is the satisfaction of knowing that I could help fulfill a very important need. Simply email me and I will forward their contact information to you.

My Themes

So, what does the future hold? Here I will admit that I cannot find any clear historical precedents against which to contrast our current state of affairs. The combination of a national lack of savings, record levels of debt, a failure to invest (in capital and infrastructure), an aging population, Peak Oil, and insolvent entitlement and pension programs has never before been encountered by humans. Worse, Alan Greenspan suckered, er, influenced the rest of the world to go along with the largest credit bubble in all of history, and so there are fewer ways to diversify internationally than might otherwise have been true.

Because the past can only provide clues, I’ve been analyzing and investing according to ‘themes’ that rely on equal parts of data, logic, and my faith that people will tend to behave as they have in the past. And let me repeat that you can count on me to change my view when the data supports a shift. Within the context of these themes, there will always be individual winners and losers. Threats and opportunities always exist side by side. Our task is to choose wisely. My major themes for the next few years are:

Theme #1: Recession, or possibly a depression, due to the bursting of the largest credit bubble in history

My concern level is “high” and stretches from right now until late 2009 to 2010. Nobody alive has ever lived through the bursting of a global credit bubble, and history offers only clues and hints as to how this all might unfold. Your guesses are as good (or as bad) as mine. The recession/depression is going to be fueled by:

- The return of household savings. If households returned to saving even just 5% compared to the current 0%, then the impact to the economy would be the loss of 3.5% of GDP. If this happened, all by itself it would contribute to one of the worst economic periods in modern times.

- Job losses. As the credit bubble bursts, credit will become harder and harder to obtain, businesses will fold, and job losses will mount. Some regions, like Detroit (cars) and Orlando (tourism) will be especially hard hit. Certain job sectors will be particularly vulnerable, especially those related to discretionary or lavish spending.

STRATEGY: Remain alert. Cut spending, reduce debt, and build savings. Be prepared to revisit portfolio assumptions and tactics on a more frequent (Quarterly? Monthly? Weekly?) basis.

WINNERS: If a deflationary recession/depression, cash and high-grade bonds. If an inflationary recession/depression, energy, commodities, and consumer staples. In either case, only a very select group of stocks will perform well. The rest will suffer big losses.

LOSERS: Stock index funds, low yielding stocks, and non-investment grade bonds. Everybody who failed to take this prospect seriously and plan properly.

Theme #2: Inflation is here and rising

(This is a near-term concern). I will remain concerned about inflation until I see my fiscal and monetary authorities begin to behave rationally. At present, the only concern I see on their parts is to ‘reflate’ the banking system at any and all costs. One of those costs is inflation. My full list of inflation concerns is as follows:

- Dollar weakness. Even if the rest of the world experiences no inflation, if our dollar falls, we will still see rising prices for oil and all of the other essential products we import.

- Supply and demand mismatch (for oil and grains especially). If there is a long-term imbalance created by the fact that the earth can no longer provide a surplus of the things that humans want/need, then prices for the desired items will consume an ever-greater share of our respective budgets.

- Structural inflation (e.g., higher oil prices make steel more expensive, leading to higher drilling costs, leading to higher oil prices….etc). Once a structural inflation spiral gets started, it is a very difficult thing to stop. Such is currently the case for food and fuel.

- Monetary inflation (growth in MZM & M3 are at historical highs). And it’s not just the US. Inflation is spiking all over the world in lockstep with exploding money supply figures. One of the hallmarks of the Great Depression was a nasty series of competitive devaluations by various countries, as they attempted to preserve their manufacturing jobs by making their products appear cheaper than others. This is a very ordinary and predictable response, as it represents both the appearance of ‘doing something’ and the path of least resistance. That makes it practically irresistible to even an above-average politician.

- Likely actions by fiscal and monetary authorities. Spending and easing, respectively, are heavily weighted towards inflation.

STRATEGY: Buy your essential items early and often. Stock up your pantry and find ways to store more items in and around your house. Don’t hold cash or cash equivalents, and avoid long-dated bonds, especially those offering negative real returns (i.e., a yield below the rate of inflation). Be prepared to move out of paper assets altogether and into tangible wealth. Productive land might be one avenue to explore.

WINNERS: Commodities, and stocks with a positive inflation sensitivity and/or strong pricing power (like energy and consumer staples companies).

LOSERS: Bonds paying a negative real rate; companies with low pricing power. Remember, it’s your real return that matters, not your nominal return. The Zimbabwe stock market is up tens of thousands of percent this year. Unfortunately, their inflation is up hundreds of thousands of percent. Stocks that don’t keep pace with inflation are another way to lose.

Theme #3: Potential banking system insolvency

(This is also a near-term concern). Yes, the Fed was able to patch things up for a while. No, the danger has not passed. Financial stocks are still getting killed in the market, and I am keeping an especially close eye on Lehman Brothers (LEH), as their stock took a particular beating at the end of last week (May 21 – 23, 2008). It won’t take too many more major financial companies going bust due to derivative-based wipeouts before the whole system goes into shock. Beyond that, here’s the basic data that gives me the most concern:

- Financial companies are holding $5 trillion (with a “t”) in level 3 assets, which utterly dwarfs the Federal Reserve balance sheet (what remains of it) and possibly even dwarfs the borrowing ability of the US government. Level 3 assets are an accounting gimmick that allow executives to place whatever value they deem appropriate on ‘hard to value’ items, like bundles of subprime mortgages that really aren’t worth all that much. Needless to say, there’s some incentive to, shall we say, be generous with the estimates of value.

- Certain derivative products, specifically credit default swaps and collateralized debt obligations, total in the tens of trillions of dollars, and their markets are in disarray. Counterparty risk is unknown and possibly unknowable. The risk here is unacceptable. If these markets spin out of control into a series of cascading cross-defaults, my main question will be, “What will happen to our financial system?” which leads to, “What will happen to financial investments?”

- Total bank capital stands at $1.1 trillion, but the potential total losses across all residential and commercial real estate are much higher than that. While a massive public bailout is probably in the cards, that will take time, and even I am shocked at how fast the housing market is deteriorating across several extremely large markets (notably all of CA, FL, Las Vegas, Phoenix, and Denver). Again, the pace of the collapse is what defines the risk here, while the magnitude is without historical precedent.

STRATEGY: Don’t have all your eggs in one basket – use several highly-rated banks. Remain liquid and alert; be prepared to access and move your funds away from troubled institutions as a tactic to avoid becoming enmeshed in a receivership process.

WINNERS: People with their dollars held by strong banks, and those who don’t have all their wealth tied up in the banking system and are holding cash, gold, silver, and other sources of liquid, non-dollar-denominated wealth completely outside of the financial system. Having strong, dependable community networks to help manage the transition period.

LOSERS: Everybody who is late to recognize that bank failures have begun and/or has their money tied up in an insolvent bank. If a generalized bank system failure does occur, we all lose, to some degree.

Theme #4: Peak Oil

This theme offers both tremendous risk and enormous opportunity. This used to be a medium-term concern of mine (2-10 years out), but has recently become a near-term concern. I happen to believe it is here right now, and the only thing that could mask it for a bit longer would be a global depression. A recession probably wouldn’t do it, though, because through all of history the largest ever yr/yr drop in global oil demand was a mere 0.4%, and that was after a particularly nasty recession back in the 1970’s…meaning it will take more than a garden-variety recession to produce the required 2%-3% drop in demand to mask declining oil production.

STRATEGY: Begin to whittle down your dependence on energy as a means of reducing the energy portion of your daily budget.

WINNERS: Energy investments of all sorts, ranging from traditional to alternative and from producers to servicers. Those with the lowest proportion of spending on energy and access to alternative modes of heating, cooling, and transportation. My prediction here is that once Peak Oil is generally recognized, solar systems will suddenly develop multi-year waiting periods.

LOSERS: An enormously wide range of companies that are built around cheap energy. Certain SUV-dependent auto manufacturers come to mind.

Theme #5: Boomer retirement

The retirement of the baby boomers will result in drawdowns that will exceed Gen-X buy-ups. To whom are the boomers going to sell all of their assets? Or, what happens when Cal-Pers (et al.) becomes a net seller rather than a net buyer? (This is a long-term concern…as in, 10 years out). Unfortunately, this retirement boom will create demands upon financial investments, concurrent with vast national needs to re-tool our energy, sewage, water, electrical, and transportation systems. Here I am expecting a toxic combination of both falling asset prices (in real terms) and rising tax bills, as our politicians attempt to simultaneously fix everything they’ve been ignoring for the past two decades.

STRATEGY: Begin reducing total exposure to everything in which boomers are overinvested. This includes stocks, bonds, and McMansions. Avoid living in places or houses that require too much reliance on energy or have especially weak or overextended governments. Vallejo, CA (now bankrupt) is an example…tax bills there are remaining constant, even as services crumble and disappear.

WINNERS: Sectors that service retiring boomers.

LOSERS: High p/e ‘growth’ stocks, low dividend stocks, and other investments whose gains largely depend on persistent and sustained buying pressure. Second homes located in less than prime areas, especially those far from urban areas and therefore requiring large amounts of gasoline to access.

The Path

While it is possible, I do not anticipate a one-way slide to the bottom, wherever and whenever that may be. I lean towards the ‘stair-step’ model, where a series of sequential shocks and relatively placid periods mark the path to the future. The three possible scenarios around which I form my thinking (and actions) are:

- No change. The future looks just like today, only bigger, and no major upheavals, shocks, or recessions happen. The Fed and Congress are successful in fighting off the deleterious effects of the bursting of the housing bubble, and everybody carries on without any major changes or adjustments. This is not a very likely outcome. Probability: 1%.

- A series of short, sharp shocks. Moments of relative calm and seeming recovery are punctuated by rapid and unsettling market plunges and marked changes in social perspective. Think of the food scarcity and riots, and you know what this looks like. One day there is low awareness about food scarcity, and the next day shortages and prices spikes are making the news. Soon enough, relative calm returns, prices fall, and order is restored, but prices somehow do not recover to their previous levels, leaving people primed and alert for the next leg of the process. I see this as the most likely path forward. Probability: 80%.

- A sudden major collapse. Under this scenario, some sort of a tipping point causes a light-speed reaction in the global economic system that requires shutting down cross-border capital flows. Banks would no longer be able to clear transfers and accounts, which would wreak all sorts of havoc upon our just-in-time society. Food and fuel distribution would be the most immediate concerns. There’s enough of a chance of this scenario occurring, and the impacts are potentially so severe, that you should take actions to minimize the impacts to yourself and loved ones. Probability: ~20%.

Which of these three scenarios will actually unfold is, of course, unknown. This is why I maintain an alert stance, and why I am constantly sifting the news and posting my thoughts in my blog. Should a serious event warrant, I will send enrolled members an alert outlining the data and actions you should consider. I have not yet sent out a single alert because no single event has crossed my threshold. If (or when) you receive one from me, it will be about something I take very seriously.

Of course, nobody can make all the changes that are required at once, or even over the next year. Rather, there is a list of things that each of us, depending on our circumstances, should consider doing over the next few years. I break them down into three tiers of actions. Tier I actions are ones that you should do immediately. Tier II are ones that you would do only after finishing the Tier I actions. Tier III are longer-term actions that come after the first two are done, or can be worked in parallel, if time, money, and energy permit.

Let me close with this: My sincerest hope is that you begin the process of adapting your lifestyle, right now, to the new future that awaits. If you are waiting for the signs to become any clearer than this, you are waiting too long.

What are you waiting for?